#16 The Bible: How to Read Scripture and the Apocrypha

Introduction: Reading the Bible Is Not Easy

“I open this book to meet with Jesus.”

Those are the words, written in gold letters, that sit atop my first Bible — an NIV Application Study Bible. When I was in high school, I received this Bible as a gift, and it became the first of many I would read, underline, understand, and misunderstand. Indeed, I wrote that little phrase on the front cover a few years after I began a daily Bible reading habit. And I embossed it there because, in college, I needed to remind myself that reading the Bible is not merely an academic exercise; it is an exercise of faith seeking understanding. Bible reading is, therefore, for doxology (praise) and discipleship (practice).

Or at least, that is how we should read Scripture.

Over the centuries following the completion of the Bible (which we will consider below), there have been many approaches to reading Scripture. Many of them have come from faith and have led to great understanding. As Psalm 111:2 reminds us, “Great are the works of the Lord, studied by all who delight in them.” And thus, studying God’s Word has always been a part of genuine faith. Yet, not all approaches to reading the Bible are equally valid or equally valuable.

As history shows, some genuine Christians have pursued the Bible in less than genuine ways. Sometimes various Christians have verged on the mystical, dabbled in the allegorical, or undercut the authority of Scripture with the traditional. Corrections, like the Protestant Reformation, were necessary because men like Luther, Calvin, and their heirs returned the Word of God to its proper place in the church, so that those in the church could engage in how to read Bible correctly. The fact remains that the Bible is the source and substance of every healthy church, and the only way to know God and to walk in his ways.

Not surprisingly, the Bible has often been attacked. In the early church, some attacks came from leaders within the church. Bishops like Arius (AD 250–336) denied the deity of Christ, and others like Pelagius (AD ca. 354–418) denied the grace of the Gospel. In more recent centuries, the Bible has been attacked by skeptics who say, “the Bible is the product of men,” or rendered obsolete by post-moderns who relegate Scripture to “one of many ways to God.” In the academy, Biblical scholars often deny the history and truthfulness of Scripture. And in popular entertainment, the Bible, or verses taken out of context, are more likely to be used for tattoos or spiritual taglines than for explanations of the world and everything in it.

Put all this together, and it is understandable why reading the Bible is so hard. In our post-Enlightenment world, one that denies the supernatural and treats the Bible like any other book, we are invited to stand over the Bible critically and question what it says. Just the same, in our sexually deviant culture, the Bible is outmoded and even hated because of the way it stands against modern secular views. Even when the Bible is treated positively, figures like Jordan Peterson read it through the lens of evolutionary psychology. Thus, it is difficult to simply read the Bible and meet with Jesus.

When I wrote that reminder for myself on the front of my Bible, I was a college student taking classes from professors of religion who denied the inspiration of Scripture. Instead, they demythologized the Bible and sought to explain away its supernaturalism. In response, I began learning about the origins of the Bible, what it contains, how to read it, and how it should inform every area of life. Thankfully, in a college that aimed to erase faith, God grew my trust in him as I sought to understand God’s Word on its own terms.

That said, by delving into the academic disciplines of theology and Biblical interpretation (a subject often described as “hermeneutics”), I needed to remind myself that the chief goal of reading the Bible is communing with the triune God. God wrote a book so that we would know him. And in what follows, it is my prayer that God would give you a truer understanding of what the Bible is, where it came from, what is in it, and how to read it. Indeed, may he give all of us a deeper knowledge of himself as we delight ourselves in his words of life.

In pursuit of knowing the God of the Bible, this field guide will answer four questions.

- What is the Bible?

- Where did the Bible come from?

- What is in the Bible?

- How do we read the Bible?

In each part, I will answer the question with an eye toward building your faith, not just providing historical or theological information. And at the end, I will join these parts together to show you why reading the Bible every day is so vital for knowing God and walking in his ways. For indeed, this is why the Bible exists: to reveal in words the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. If you are ready to learn more about him, we are ready to talk about the Bible.

Audio Guide

Audio#16 The Bible: How to Read Scripture and the Apocrypha

Part 1: What Is the Bible?

The answer to this question is manifold, for the Bible has played a multifaceted role in shaping the world. In addition to being “the Word of God written” (WCF 1.2), the Bible is also a cultural artifact, a bulwark for civilization, a literary masterpiece, an object of historical inquiry, and sometimes a target for ridicule. Yet, for those who treat the Bible as a priceless treasure, and for churches that build themselves upon the fullness of its counsel, the Bible is more than a book for inspiration or religious devotion.

The Bible is, as Hebrews 1:1 begins, the very words of God, spoken to the fathers by the prophets “long ago, at many times and in many ways.” Indeed, God spoke to his people in ancient times, but writing hundreds of years after God spoke to Israel out of the fire (Deut. 4:12, 15, 33, 36), the author of Hebrews could say, “in these last days he has spoken to us by his Son.”

In this way, the Bible is not just a religious book deposited all at once. Nor is it a work of literature with no traction in history. Rather, the Bible is the progressive revelation of God, which perfectly interprets his acts of salvation and judgment in the world. As we look at the structure of the Bible, we see a cohesive narrative.

And more, the thirty-nine books of the Old Testament and New Testament divisions work together; the former played a unique role in preparing the way for the eternal Word to take on flesh and dwell among us (John 1:1–3, 14), and the twenty-seven books written after his ascension bore testimony to Christ’s life, death, resurrection, and exaltation. Understanding this connection is vital for any Bible reading plan

you might choose to follow. Even today, the Word of God continues to accomplish its purposes of redemption, even as the revelation of God’s Word came to a close at the end of John’s Apocalypse

(see Rev. 22:18–19).1

For this field guide, we will not delve into all the ways the Bible has shaped the world and has itself been shaped by the world.2 Instead, our time will be spent answering the theological question: What is the Bible, as the church has received it? To that question, I will offer three answers — one from the Protestant confessions, one from the Biblical canon, and one from the testimony of the Holy Spirit who inspired the Bible.

According to the Confessions

In 1517, a German monk with a mallet nailed the 95 Theses to the Wittenberg Castle Door.3 Martin Luther, a trained theologian and studious pastor, was concerned with the way the Roman Catholic Church had misled him and others to believe that righteousness was achieved through an endless maze of sacraments, instead of faith alone in the finished work of Christ alone — all by the grace of God. Indeed, by his study of Scripture, Luther had become convinced that the Roman Catholic Church had lost the Gospel and its message of justification by faith alone.4 Accordingly, he ignited the Protestant Reformation with his 95 Theses.

In the decades that followed, the Protestant Reformation recovered the Gospel and its source, the Bible. Unlike the Roman Catholic Church, which affirmed the Bible’s divine origin and authority but also put church tradition on the same level as the Bible, men like Luther, John Calvin, and Ulrich Zwingli began to teach that the Bible was the only source of inspired revelation. Whereas the Roman Catholic Church taught that God spoke through two sources, the Bible and the Church, the Reformers rightly affirmed Scripture as the only source of special revelation. As Luther famously stated,

Unless I am convinced by the testimony of the Scriptures or by evident reason — for I can believe neither pope nor councils alone, as it is clear that they have erred repeatedly and contradicted themselves — I consider myself conquered by the Scriptures adduced by me and my conscience is captive to the Word of God.5

Indeed, Luther’s advocacy for the Bible as God’s Word was echoed by all the Reformers. Today, the heirs of the Reformation continue to hold Scripture as God’s inspired and authoritative Word. The best place

to see that conviction is in the confessions that came from the Protestant Reformation, such as the Belgic Confession, the Thirty-Nine Articles, and the Westminster Confession of Faith, which all affirm Sola Scriptura. Yet, to offer my own tradition: The Second London Baptist Confession (1689).

In the opening paragraph of the first chapter, the ministers confessed their faith in God’s Word:

- The Holy Scriptures are the only sufficient, certain, and infallible standard of all saving knowledge, faith, and obedience… Therefore, the Holy Scriptures are absolutely necessary, because God’s former ways of revealing his will to his people have now ceased.

In this statement, they affirmed the sufficiency of Scripture, necessity, clarity, and authority. These four attributes articulate how Protestants view the Bible as “the word of God written” (WCF 1.2). Those who take the Word of God seriously treat it as divine truth in human words because they believe the testimony of Scripture itself.

According to the Canon

Protestants do not believe that church tradition is sufficient to develop beliefs about the Bible. Instead,

we believe Scripture bears witness to itself. For instance, 2 Timothy 3:16 says that all Scripture is “God-breathed” (theopneustos), asserting the inspiration of Scripture. Likewise, 2 Peter 1:19–21 identifies the Holy Spirit as the source for the prophets. Paul also notes in Romans 15:4 that what was written in former days was for our instruction and hope.

The Old Testament and New Testament are inextricably linked. The Law, the Prophets, and the Writings — the three parts of the Hebrew Bible — all point to Christ. Jesus identifies Himself as the subject of the Old Testament (John 5:39) and the one to whom all scriptures point (Luke 24:27, 44–49).

Jesus also anticipated the Holy Spirit coming to bear witness about Him (John 15:26; 16:13). This Spirit

of truth would remind the disciples of His words, ensuring that we can trust the Bible as God’s Word.

According to the Testimony of the Spirit

If the Bible is its own source of authority, is this not circular reasoning? While an argument for the Bible from the Bible is circular, it is not a fallacy. All claims to ultimate authority are broadly circular. If the Bible depended on an outside entity for its authority, that entity would become the authority over the Bible. This was the error of the Roman Catholic Church, which claimed authority to decide the canon and interpret it through tradition.

By contrast, the Reformers spoke of the Bible’s “self-attestation.” Because the Holy Spirit who prompted the inspiration of Scripture continues to impress its truth on souls today, we can have real confidence.

As we engage in daily Bible reading, the Spirit “drives away the misty darkness of errors” and instructs

us in truth.

By contrast, John Calvin and the Reformers spoke of the Bible’s “self-attestation.”6 The Bible is the Word of God because the Bible declares itself to be so, and its legitimacy is found in the way that its testimony is proven by all that it says about everything else. Equally, because the Holy Spirit who inspired the Bible continues to impress its truthfulness onto souls who hear it today, we can know that the Bible is God’s Word. In other words, because the origin of the Bible (an objective reality) and one’s confidence in the authenticity of the Bible (a subjective belief) both come from the same source (the Holy Spirit), we can have real confidence that the Bible is God’s Word. As the Reformer Heinrich Bullinger put it,

If, therefore, the word of God sounds in our ears, and there the Spirit of God shows forth his power in our hearts, and we in faith do truly receive the word of God, then the word of God has a mighty force and a wonderful effect in us. For it drives away the misty darkness of errors, it opens our eyes, it converts and enlightens our minds, and instructs us most fully and absolutely in truth and Godliness.7

Those willing to listen to the authors of Scripture will find a unified testimony of some forty men, writing in three different languages (Hebrew, Greek, and some Aramaic) over the course of fourteen hundred years. The likelihood that such a composition could be crafted cogently by human authors alone is impossible.

Still, the visible evidence of literary unity is powerful, but we remain dependent on the living God to reveal himself to us. And therefore, the testimony of the Spirit is ultimately what causes us to believe the Bible (John 16:13). This internal work of the Spirit is vital as we seek to understand how to pray for insight and illumination while we study.

In sum, then, God has spoken, and his words are found in the sixty-six books of the Bible. Or at least, those are the books that Protestants recognize in their Bible. Understanding this divine origin changes how to read Bible passages; we don’t just look for information, but for the voice of our Creator.

—

Discussion & Reflection:

- How would you answer the question “What is the Bible?” How would you put the above material in your own words?

- Was anything that you just read new or surprising to you? What challenged you?

- How does the truth that the Bible is God’s very Word affect the way you read it? Think specifically about your daily Bible reading—does this conviction change your posture or your expectations?

—

Part 2: Where Did the Bible Come From?

When we talk about the Bible, we are talking about the books of the Biblical canon. As R. N. Soulen has defined the term, a canon is “collection of books accepted as an authoritative rule of faith and practice.”8 In Hebrew, the word canon comes from the word qaneh, which can mean “reed” or “stalk.” In Greek, the word kanon often has the idea of being a rule or principle (see Gal. 6:16). Connecting both languages, Peter Wegner notes, “Certain reeds were also used as measuring sticks, and thus one of the derived meanings of the word [qaneh, kanon] became ‘rule.’”9

And so this explains the word’s background. But what about canonicity? How does a book “make the cut,” so to speak? That question is vital for understanding the Bible, the church, and who authorizes whom.

In answer to this set of questions, it is tempting to think that the church authorizes the Bible and decides what books should be in the canon. This is what the fourth session at the Council of Trent did in recognizing the books of the Apocrypha, and it is also what Dan Brown did in his fiction, suggesting that certain texts like the Gospel of Thomas were excluded by mere human politics. Even the language of the Apocrypha (the hidden things) hints at this kind of thinking, but actually, it is misguided.

As we noted above, the source of the Bible is God himself, and the Spirit is the one who moved the authors to write what they wrote. To measure twice before cutting once, the church did not authorize the books that would compose the canon; rather, the churches (led by the Spirit) recognized the books of the Bible as being inspired by God. In other words, the church did not create the Bible; the Bible, as the Word of God, created the church. This is a simple distinction, but one with massive implications for how to read Bible correctly.

What we think about the Biblical canon will largely determine how we approach Bible reading. Are the books of the Bible the work of God, recognized by men? Or is the canon the work of men? Put succinctly, individual assemblies in the first centuries had to decide which letters and Gospels were the result of the inspiration of Scripture. This is even seen within the text:

– 1 Corinthians 14:37: Paul insists that the spiritual must acknowledge his writings as a command of the Lord.

– 2 Peter 3:15–16: Peter recognizes Paul’s letters as Scripture.

– 1 John 4:6: John declares that those who know God listen to the apostolic testimony.

The New Testament teaches us that the Word of God was not something actively decided by the church, but something passively recognized. The words of the apostles were confirmed by works of the Holy Spirit (Heb. 2:4; 2 Cor. 12:12). Over three centuries, from the resurrection to the Easter Letter of Athanasius in 367 AD, the composition of the canon was a process of reception, not creation.

Because the Hebrew Bible canon was already a solid foundation in the days of Christ, the early church could focus on the New Testament testimony. In the rest of this section, I will offer three reasons for each testament as to why we can have confidence in the Old Testament and New Testament as we pursue a daily Bible reading plan.

Old Testament

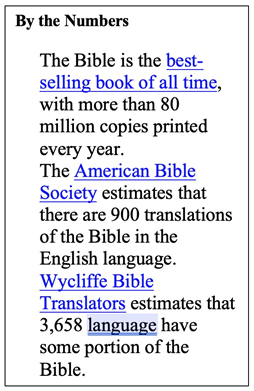

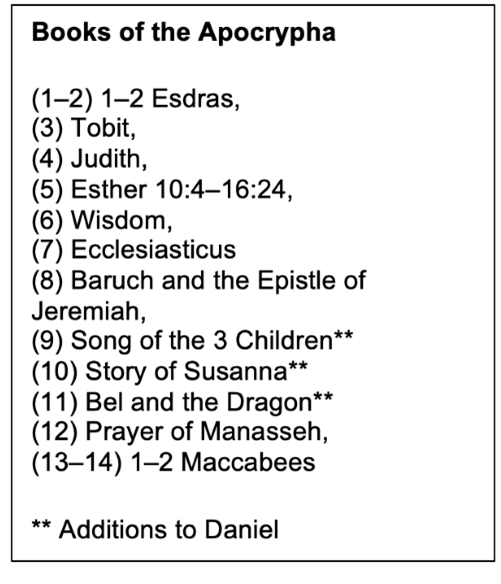

The New Testament consistently testifies that the books of Moses (Torah), the words of the Prophets (Naviim), and the Psalms (Ketuviim) were the canonical books of the Old Testament.10 For this reason, “there is little to no [scholarly] dispute about the core of the Old Testament we see the New Testament use.”11 Nevertheless, let me offer three reasons why we should have confidence that these additional fourteen books of the Apocrypha are withheld from the canon.

1. First, by the time the books of the Apocrypha had been written, the Spirit of God had stopped speaking.

As noted by multiple sources, the Spirit of God no longer spoke after Malachi. For instance, the Babylonian Talmud declares, “After the latter prophets Haggai, Zechariah, and Malachi had died, the

Holy Spirit departed from Israel, but they still availed themselves of the voice from heaven” (Yomah 9b). Likewise, the historian Josephus notes in Against Apion, “From Artaxerxes to our own times a complete history has been written, but has not been deemed worthy of equal credit with the earlier records, because of the failure of the exact succession of the prophets’’ (1.41). Similarly, 1 Maccabees, one of the Apocryphal books, views its own time period as devoid of prophets (4:45–46). Thus, it is clear that the things written between Malachi and Matthew did not contain inspired Scripture.

2. Second, the early church made a clear distinction between canonical and non-canonical books.

From AD 382–404, Jerome translated the Bible into Latin. In time, his translation became known as the Latin Vulgate, a term signifying the common language of the people.12 In his translation work, he came across the “Septuagintal plus,” the extra books included in the Greek translation of the Old Testament.13 Sensing a need to translate from the original Hebrew and not rely solely on the Greek translation, he quickly discerned that not all of the books found in the Septuagint were of equal value. Thus, he limited the canonical books to the thirty-nine found in today’s Protestant Bibles.14 In turn, he accepted the apocryphal books as having a place for historical instruction, but not for determining doctrine.15

The canonical books alone possessed such authority.

In the centuries that followed until the Reformation, Jerome’s distinction between canonical and non-canonical books was largely lost. As his Latin translation became the people’s book, Apocryphal books were often included.16 Accordingly, the medium formed the message, and the Apocrypha became part

of the accepted canon. This inclusion would sponsor erroneous doctrines in the Roman Catholic Church, doctrines like praying for the dead (2 Macc. 12:44–45) and salvation by almsgiving (Tobit 4:11; 12:9).

We can see why the early church made a clear distinction between canonical and noncanonical books.

3. Third, the Reformation recovered the Hebrew Bible.

When Reformers like Martin Luther began championing Sola Scriptura (“Scripture alone”), the question of canon returned. And among Protestants, the Apocrypha was returned to its proper place — a selection of books useful for their history, but not for authoritative doctrine. This is evident in the way that Luther, Tyndale, Coverdale, and other Protestant Bible translators followed the distinction of Jerome, and relegated the Apocryphal books to appendices in their respective Bible translations.17

By contrast, the Council of Trent (1545–63) recognized these books as authoritative for doctrine and condemned anyone who would question their place. Additionally, the first Vatican Council (1869–70) reinforced the point and argued that these books were “inspired by the Holy Spirit and then entrusted

to the church.”18 This divide still stands between Protestants and Roman Catholics. Yet, for reasons stated above, it is best to follow Jerome’s distinction that the books of the Apocrypha are neither necessary nor appropriate for establishing doctrine. Rather, they are merely helpful for providing historical background to the story of God’s work among the people of Israel.19

New Testament

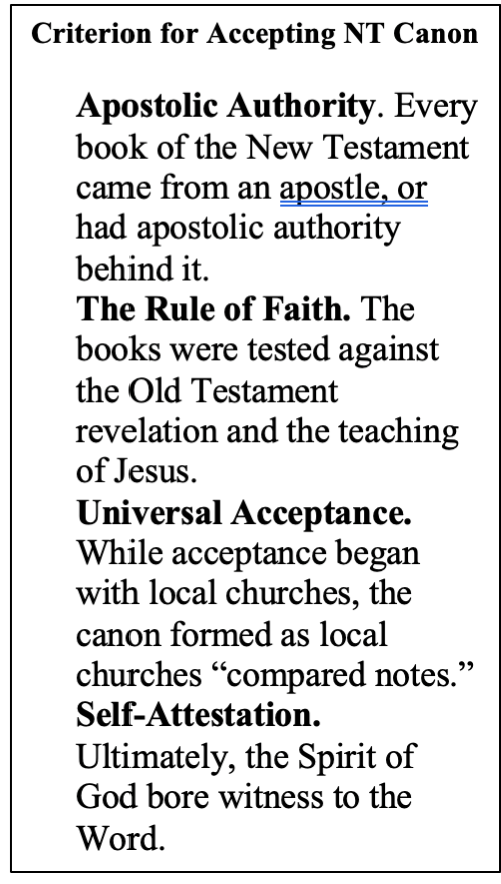

If the New Testament confirms the books of the Old Testament, what confirms the books of the New?

At first blush, this question seems to be more challenging. But just as Jesus and the early church could recognize that the Scriptures came from the Holy Spirit (2 Pet. 1:19–21; cf. 2 Tim. 3:16) over against those books that did not come from the Spirit, so too the early church could recognize Gospels and Epistles that came from the apostles and those that did not.

1. First, the origins of the canon are evident in the New Testament itself.

For instance, in 1 Timothy 5:18, Paul cites from Moses and Luke, referring to both of them as Scripture: “For the Scripture says, ‘You shall not muzzle an ox when it treads out the grain,’ [Deut. 25:4] and, ‘The laborer deserves his wages’ [Luke 10:7].” Similarly, Peter associates Paul’s letters with Scripture (2 Pet. 3:15–16).

And this reference comes right after Peter states, “that you should remember the predictions of the holy prophets and the commandment of the Lord and Savior through your apostles” (2 Pet. 3:2). In other words, Peter understands the apostles to be carrying the very words of Christ, and he associates the apostles with the holy prophets of the Hebrew Bible.

In sum, then, the Bible itself bears witness to the apostolic writings as God’s Word. This internal evidence is a cornerstone of the inspiration of Scripture and provides a firm foundation for any daily Bible reading plan. By seeing how the apostles viewed each other’s work, we gain clarity on the unity of the Old Testament and New Testament.

2. Second, as with the Apocrypha, the other books written in the centuries after Christ do not measure up.

As Köstenberger, Bock, and Chatraw note, the Letter of Ptolemy, the Letter of Barnabas, and the Gospels

of Thomas, Philip, Mary, and Nicodemus all demonstrate themselves to be “leagues apart” from inspired Scripture.20 For instance, citing the most famous extra-Biblical Gospel, they write of the Gospel of Thomas:

This book is not a Gospel in the pattern of the four Gospels of Scripture. It has no storyline, no narrative, no account of Jesus’s birth, death, or resurrection. It contains 114 sayings allegedly attributed to Jesus, and though some sound like what you might hear in Matthew, Mark, Luke, or John, many are strange and bizarre. Broad consensus places its writing in the early to late second century, but it never factored into canonical discussions. In fact, Cyril of Jerusalem specifically warned against reading it in the churches, and Origen characterized it as an apocryphal Gospel. The following statement [from Michael Kruger] sums it up: “If Thomas does represent authentic, original Christianity, then it has left very little historical evidence of that fact.”21

3. Third, the early church quickly reached a consensus on the canon.

Indeed, due to multiple factors, the early church reached a consensus on the canon over many generations. While Christian books like the Letter of Barnabas and The Shepherd of Hermas were appreciated, and occasionally read in some churches, they were not confused with Scripture. Like with the Apocrypha, Jerome noted that these “ecclesiastical” writings were good “for the edification of the people but not for establishing the authority of ecclesiastical dogmas.”22

Throughout the first few centuries after Christ, a growing list of recognized books emerged. Indeed, as listed here, the church not only cited the apostles in their sermons, letters, and books, but they would occasionally list the books as well (e.g., the Muratorian Canon).23 And thus, “the books of the New Testament were recognized (not selected) as cream that had risen to the top, used by churches because they were seen to have unique and special value.”24 To cite Jerome once more,

Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John are the Lord’s team of four, the true cherubim (which means ‘abundance of knowledge’), endowed with eyes throughout their whole body; they glitter like

sparks, they flash to and fro like lightning, their legs are straight and directed upward, their backs are winged, to fly in all directions. They are interlocked and hold on to one another; they roll along like wheels within wheels; they go to whatever point the breath of the Holy Spirit guides them.

The apostle Paul writes to seven churches (for the eighth such letter, that to the Hebrews, is placed outside the number by most); he instructs Timothy and Titus; he intercedes with Philemon for his runaway slave. Regarding Paul, I prefer to remain silent rather than write only a few things.

The Acts of the Apostles seem to relate a bare history and to describe the childhood of the infant church; but if we know that their writer was Luke the physician, ‘whose praise is in the Gospel, ’ we shall observe likewise that all their words are medicine for the sick soul. The apostles James, Peter, John, and Jude produced seven epistles, both mystical and concise, both short and long — that is, short in words but long in thought so that there are few who are not deeply impressed by reading them.

The Apocalypse of John has as many mysteries as it has words. I have said too little in comparison with what the book deserves; all praise of it is inadequate, for in every one of its words manifold meanings lie hidden.25 In this list, Jerome gives us the twenty-seven books of the New Testament, but he also hints at their respective glories. And thus, it moves us to consider why the canon matters.

Why the Canon Matters

We have labored to answer the question, “Where did the Bible come from?” for a very basic reason: namely, how one understands the Bible’s formation, source, and contents determines how one reads — or doesn’t read! — the Bible’s message. Bible readers who are serious about knowing God cannot have confidence to believe what Scripture says or conviction to do what it commands unless they know that the Bible is the inspired and authoritative Word of God and not the fabrication of religious men.

On this point, the Biblical canon matters immensely. It serves as the boundary that protects the sufficiency of Scripture, ensuring that we neither add to nor take away from God’s complete revelation. Without a defined canon, a daily Bible reading habit would lack the firm foundation of knowing exactly which words are God’s words.

As we finish this section, let’s expand on the importance of the canon with three implications. These points will clarify how to read Bible texts with the assurance that you are handling the genuine inspiration of Scripture, rather than late additions like the Apocrypha or the Gospel of Thomas, which do not bear the marks of apostolic authority.

Understanding the canon is not just for scholars; it is essential for every believer’s Bible reading plan.

It provides the historical and theological “coordinates” needed to navigate the Old Testament and New Testament faithfully.

1. First, the formation of the canon undergirds the unity of God’s Word.

Amazingly, Scripture was written by about 40 human authors over roughly 1,400 years. But behind all of them is the one divine author who breathed out every word (2 Tim. 3:16; 2 Pet. 1:19–21). Indeed, the unity of Scripture is not found in a single deposit of information or a text devoid of literary tension. Rather,

the unity of the Bible comes from the fact that it “has God for its author, salvation for its end, and truth, without any mixture of error, for its matter” (BFM 2000). That is to say, over time, God inspired a series

of interconnected books that came to form a unified yet variegated revelation.

The formation of the canon, therefore, serves to undergird the unity of God’s Word, such that readers of the Book can know they are reading a drama of redemption. As God revealed himself to Moses, then to the prophets on the way to Christ, and then through the ministry of the apostles, there are tensions, events, and instructions that may appear contradictory. In one place, God says don’t eat anything unclean (Lev. 11); in another, he says the direct opposite (Acts 10). Bacon is back on the menu! If this appears disjointed or contradictory, that is only because one hasn’t yet learned how this part of the storyline unfolds.

In truth, the Bible is unified by a story rather than a set of timeless abstractions. And thus, understanding how the canon was formed through the ages of redemption reinforces confidence in the unity of Scripture. This is vital for any Chronological Bible reading plan, as it helps the reader see the progress of God’s plan. At the same time, it trains us in how to read Bible passages by resolving legitimate tensions through the lens of progressive revelation—a point we will consider below. This organic unity is what makes daily Bible reading so rewarding; we aren’t just reading fragments, but a singular, divine narrative.

2. Second, the source of the canon undergirds the authority of God’s Word.

If the canon was composed over time, as God spoke to the fathers through the prophets at many time and in many ways (Heb. 1:1), and if the canon was closed because the full and final revelation of God has come in Jesus Christ (Heb. 1:2; cf. Rev. 22:18–19), then we must acknowledge that this book is unlike any other. Indeed, the debate over the canon matters because what Scripture says, God says. This was the point that B. B. Warfield made in a famous essay entitled, “‘It Says:’ ‘Scripture Says:’ ‘God Says,’”26, and it can be found throughout the New Testament, where Jesus and his apostles appeal to Scripture as the authoritative Word of God.

For this reason, it matters that we know what is in the Bible and what is not. For, as we will see, when we follow the Reformation principle of letting Scripture interpret Scripture (i.e., the analogy of Scripture), we must define and explain Scripture by other passages that are actually inspired by God. Biblical theology, “the discipline of letting Scripture interpret Scripture and reading the whole Bible according to its own literary structures and unfolding covenants,” depends on having a Bible with fixed boundaries.27 To deny the canon, therefore, or to place canonical and non-canonical books on the same level leads to faulty interpretations and theological conclusions. Something I have labeled “the butterfly effect of Biblical theology.”

3. Third, the arrangement of the canon reveals the message of God’s Word.

If God is the source of the canon and the formation of its contents was under his divine providence, then we should not ignore the arrangement of God’s Word. In other words, just as Paul can make a theological argument for justification by grace alone by simply recognizing the way that the law of Moses was added 430 years later to the covenant made with Abraham (Gal. 3:17), so we should recognize that the literary and historical arrangement of the Biblical canon has interpretive significance. In other words, instead of seeing the Bible as a collection of books accidentally arranged, we should see how the whole canon reveals a message.

This is true in books like the Psalms and the Twelve, otherwise known as the minor prophets, but it is

true with the whole Bible too. As Old Testament scholar Stephen Dempster has observed, “Different arrangements generate different meanings.” And thus, “on a larger scale, the interpretive implications of the different arrangements of the Hebrew Tanakh and the Christian Old Testament have been noted.”28 Dempster’s observation is critical for reading the Bible, even as it introduces a wrinkle that exceeds the bounds of this field guide.

Dempster, along with others, has noted the way in which the Hebrew was arranged differently from the standard English Bible. The former has twenty-two books, the latter thirty-nine. To date, no publishers have offered an English Bible arranged like the Hebrew Bible. Nevertheless, awareness of this difference

is worthwhile. For not only does the Hebrew arrangement predate the English order, but this literary arrangement tells a theological story and provides a “hermeneutical lens through which its contents can be viewed.”29

Finally, it should be noted that this difference in canonical arrangements should not undermine our confidence in Scripture, but it should remind us of how Scripture came together. When we compare one passage with another, one part of the Bible with another, arrangement does matter. And this will be most evident as we come to Part 4 (How should we read the Bible?). Before going there, we have one more question to answer: What is (not) in the Bible?

—

Discussion & Reflection:

- How did this section strengthen your faith in God’s Word?

- How would you respond to a friend who thinks the books of the Apocrypha carry equal authority

as the sixty-six canonical books?

—

Part 3: What Is (Not) in the Bible?

I will not attempt to answer this question in the positive here, for to answer “What is in the Bible?” would require a full engagement with all sixty-six books. Indeed, there is a need for such engagement, and there are many helpful resources on this point, including Study Bibles,30 Bible surveys,31 and, most profitably, Biblical theologies. The reason I believe Biblical theologies are most helpful is that they do more than survey the text; they provide a lens through which we can read Scripture and understand its overarching message. Of all the good books on the subject, I would begin with these three.

– Graeme Goldsworthy, According to Plan: The Unfolding Revelation of God in the Bible (2002)

– Jim Hamilton, God’s Glory in Salvation through Judgment: A Biblical Theology (2010)

– Peter Gentry and Stephen Wellum, God’s Kingdom through God’s Covenants: A Concise Biblical Theology (2015)

While a positive Biblical theology will help anyone know what is in the Bible and how it fits together,

it is equally important to know what is not in the Bible. That is to say, if we come to the Bible with wrong expectations, we are susceptible to misreading Scripture or giving up reading Scripture entirely because it does not match our preconceived ideas.

However, if we can clear away some false expectations of Scripture, it will prepare us to read the Bible well. Understanding the boundaries of the Biblical canon ensures that we don’t accidentally treat human traditions or cultural myths as having the same weight as the inspiration of Scripture.

Misconceptions often arise when readers expect the Bible to be a modern science textbook, a simple “rule book” for every specific life decision, or a collection of disconnected moral fables. By identifying what is absent—such as the Apocrypha in the Protestant tradition or modern cultural additives — we protect the sufficiency of Scripture. This clarity is vital to a healthy daily Bible reading habit, as it allows the text to speak for itself without being muffled by our own assumptions.

Recognizing these boundaries helps us focus on the core message: the Old Testament and New Testament unity that points to the person and work of Jesus Christ.

And to help us avoid misreading the Bible, let me offer five considerations from Kevin Vanhoozer.

In his illuminating book, Pictures at a Theological Exhibition: Scenes of the Church’s Worship, Witness, and Wisdom, Vanhoozer reminds us that the Bible is a communication from God, the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, to the people made in his image. In other words, it is not merely a religious text or handbook for spiritual living. Rather, citing J. I. Packer, he summarizes the Bible in one sentence: “God the Father preaching God the Son in the power of God the Holy Ghost.” And with this positive statement in place,

he provides five things the Bible is not.32

Building on the idea of clearing away false expectations, here are five essential truths about what the Bible is—and what it is not:

- Scripture is not a word from outer space or a time capsule from the past, but a living and active Word of God for the church today. It is not a relic to be admired from a distance, but a present-tense address from the Creator to His people.

- The Bible is both like and unlike every other book: it is both a human, contextualized discourse

and a holy discourse ultimately authored by God and intended to be read in canonical context. It possesses a dual authorship—human and divine—that requires us to respect its history while submitting to its authority. - The Bible is not a dictionary of holy words but a written discourse: something someone says to someone about something in some way for some purpose. We shouldn’t treat it like a reference manual for isolated “magic words,” but as a series of intentional communications.

- God does a variety of things with the human discourse that makes up Scripture, but above all, he prepares the way for Jesus Christ, the climax of a long, covenantal story. From the first pages of the Hebrew Bible to the final vision of Revelation, the narrative arc is intentionally directed toward the Savior.

- God uses the Bible both to present Christ and to form Christ in us. The goal of our daily Bible reading is not merely the accumulation of facts, but transformation into the image of the Son.

These principles shift our focus from a “what can I get out of this” mentality to a “what is God saying to me” posture. When we understand how to read Bible genres as parts of this grand covenantal story, the Old Testament and New Testament become a unified voice shaping our faith today.

Indeed, getting the Bible right does not secure good interpretation or practice, but getting the Bible wrong will lead to errors large and small. So we should aim to rightly understand what Scripture is and what it is intended to do — namely, to lead us to Christ and make us like him. This means we must read the Bible with faith, hope, and love. Or to draw out the logical implications, we read the Bible with hope that the God who spoke in his Word will produce in us faith that leads to love.

Truly, no other book in the world can do that. And if we treat the Bible like any other book, we will misread it. Knowledge may increase, but faith, hope, and love will not. At the same time, if we do not

give attention to the grammatical and historical nature of the Bible as a book, we are liable to misread its contents as well. Accordingly, we need to read the Bible wisely, but such wisdom depends on knowing what the Bible is and what it is not.

To return to Packer’s definition of Scripture, the Bible is the Father’s Word to us, inspired by the Spirit,

to bring us to the Son, so that by God’s Word in human words we might know him and be conformed into his image. In this way, the Bible is a book given to illicit praise to the triune God (doxology) and to cultivate faith, hope, and love in God’s people (discipleship). And with these two orientations in place,

we are now ready to consider how to read the Bible.

—

Discussion & Reflection:

- Are you ever tempted to think wrongly about what the Bible is? Do any of the five items listed above describe things you think or have thought before?

- Do you read the Bible “with hope that the God who spoke in his Word will produce in us faith that leads to love”? How might that change the way you engage with Scripture?

—

Part 4: How Should We Read the Bible?

As with the first three parts, the question at hand — how to read Bible? — requires more than can be offered here. Nevertheless, I will offer three practical steps for reading the Bible as God’s Word, keeping in mind the inspiration of Scripture.

– Discover the grammatical and historical context of the passage.

– Discern where the passage is found in the covenantal history of the Bible, tracing the story from the Old Testament and New Testament.

– Delight in the way that this passage brings you to a fuller knowledge of Jesus Christ, making it the heart of your daily Bible reading and any Bible reading plan.

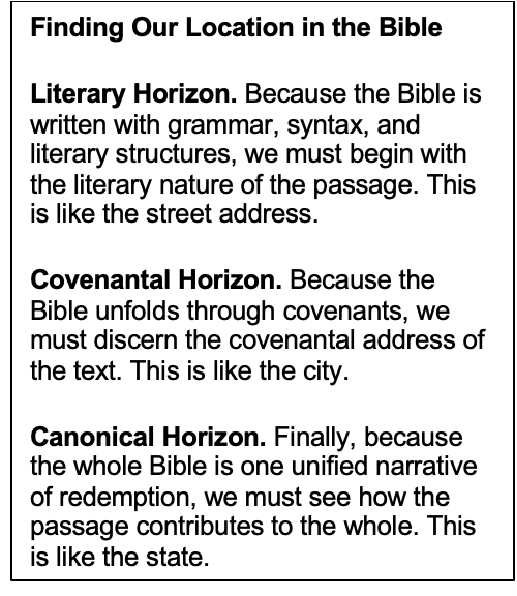

These three “steps” can be described as the textual, covenantal, and Christological horizons of any given passage.33 In order, each serves as a stepping stone towards uncovering the meaning of a text, its placement in redemptive history, and its relationship to God revealed in Christ. Together, they provide a consistent approach to reading any part of the Bible, for those who are willing to “study” the works revealed in God’s Word (Ps. 111:2).

Such a consistent approach is helpful because understanding the Bible on its own terms takes work. Because every Bible reader brings his or her own preconceived notions to Scripture, any proper method for reading will help us see what is in the Bible and avoid imposing our own ideas and interests on it.

To do that, I have found this threefold approach to be remarkably helpful.34 So, we will look at each.

Yet, before taking the first step, let me offer a word of encouragement to those just beginning to read the Bible. Whether you are starting a new Bible reading plan or simply making daily Bible reading a part of your life, understanding how to read Bible texts will help you see the divine inspiration of Scripture on every page.

Preparing to Read the Bible: Cultivating a Heart for God’s Word

While reading the Bible well takes discipline and skill, it begins with something far more basic — simply reading the Bible. Just as running precedes running well, and playing the piano at home precedes playing the piano for others, so too reading the Bible well begins with the simple act of reading.

Therefore, I would encourage anyone who is just beginning to read Bible to trust God, ask for his help, and read with faith. God promises to reveal himself to anyone who seeks him with a true heart (Prov. 8:17; Jer. 29:13). If you read Scripture, you will learn that we cannot seek God without his help (Rom. 3:10–19), but you will also discover that God delights to show himself to those who approach him with faith (Matt. 7:7–11; John 6:37). God is not stingy toward those who seek in faith.

Knowing that, those who read the Bible should pray and ask God to make Himself known to them. The Spirit is the one who gives life and light, and because reading the Bible is a spiritual endeavor, new readers should ask for his divine aid. And then, with faith that he hears and answers such a prayer, they should read, read, and read some more. Just as physical growth takes repeated meals and bodily motion before size and strength are registered in a body, so spiritual growth and Biblical understanding take time too.

Thus, the most important thing for reading the Bible is cultivating a heart for God’s Word. And there is no better place to do that than Psalm 119. If reading the Bible is new for you, take one stanza (eight verses) of Psalm 119, read it, believe it, pray it, and then begin reading the Bible.

Additionally, having a consistent time, place, and Bible reading plan or schedule will make reading more enjoyable.35 Over the years, I have learned that daily Bible reading is not simply a habit to develop; it is a heavenly meal to enjoy. Just as we eat food for physical strength and pleasure, so Scripture should be enjoyed the same way. As Psalm 19:10–11 puts it, “More to be desired are they than gold, even much fine gold; sweeter also than honey and drippings of the honeycomb. Moreover, by them is your servant warned; in keeping them there is great reward.”

With this promise in mind, let me encourage you to taste and see how good the inspiration of Scripture is. As you read, I offer these next three steps to help you make the most of reading the Bible well.

The Textual Horizon: Discovering the Meaning of the Text

All good Bible reading begins with the text. And a key text for observing Biblical interpretation in action is Nehemiah 8. Describing the action of the priests, who were commissioned to teach people of Israel (Lev. 10:11), Nehemiah 8:8 reads, “They read from the book, from the Law of God, clearly, and they gave the sense, so that the people understood the reading.” In the historical context, the people needed re-education in God’s ways when they returned from exile. Even before the exile, attention to the Law had been lost (cf. 2 Chron. 34:8–21), and now delivered from captivity, the sons of Israel were not much better off. Hebrew had been lost in the exile; Aramaic was the new lingua franca, and so Nehemiah had the Law read, and the priests “gave the sense” of its meaning.

Like Ezra himself (Ezra 7:10), these Levitical leaders helped the people understand and apply the Law of God. As the Law commanded them to do (Lev 10:11), they were explaining what the Law meant. And thus we have a true example of Biblical exposition, where the text is explained line by line. In particular, the meaning of a passage is found in the prose, the poetry, and the propositions found in sentences, stanzas, and strophes. In short, how to read Bible literature effectively begins by paying attention to the literary and historical context of a given passage.

This focus on the original intent is a vital part of the inspiration of Scripture. When you engage in daily Bible reading, you are not just looking for a personal “feeling,” but for the “sense” that God originally communicated through the human authors. Whether you are following a specific Bible reading plan or studying a single book, understanding this context helps you rightly handle the Bible and its message.

And importantly, this way of reading is not just produced outside the Bible; it is actually found within it. Deuteronomy and Hebrews both demonstrate Biblical exposition, which is another way of describing reading the Bible with precision and application. For instance, Deuteronomy 6–25 expounds the Ten Commandments (Exodus 20; Deuteronomy 5), and Hebrews is a sermon that expounds and relates multiple passages from the Old Testament.36

On this basis, we can learn from Scripture how to read Bible narratives and teachings. And when we

read the Bible, we should begin at the textual horizon, where we pay careful attention to the author’s intentions, the historical context of the audience, and the aim of the book, written from the author to the audience. In this way, we should first pay attention to what the author says (the textual horizon) and then when he says it (the covenantal horizon).

The Covenantal Horizon: Discerning the Storyline of God’s Covenant History

Zooming out from the textual horizon, we come to the covenantal horizon, or what others have called

the epochal horizon.37 This horizon recognizes that the Bible is not merely a catalog of timeless truths. Rather, it is a progressively revealed testimony about God’s redemption in history. It is intentionally written along the lines of a multi-faceted promise fulfilled in Christ. As Acts 13:32–33 says, “And we

bring you the good news that what God promised to the fathers, this he has fulfilled to us, their

children, by raising Jesus.”

In recent centuries, this progressive revelation has been variously described as a series of dispensations

or covenants. And while various traditions have understood the Biblical covenants differently, the Bible is unmistakably a covenantal document, comprised of two testaments (Latin for “covenant”), and centered on the new covenant of Jesus Christ.

Therefore, it fits the Biblical storyline to understand it as a series of covenants. In fact, from an overview of the Bible, we can lay out redemptive history along six covenants, all leading to the new covenant of Christ.

– Covenant with Adam

– Covenant with Noah

– Covenant with Abraham

– Covenant with Israel (mediated by Moses)

– Covenant with Levi (i.e., the priestly covenant)

– Covenant with David

– The New Covenant (mediated by Jesus Christ)

These covenants are listed in chronological order and can be shown to possess organic unity and theological development over time. For matters of reading the Bible, it is necessary to ask, “When is this text taking place, and what covenants are in force?”

This question requires the reader to grow in his or her understanding of the covenants, their structure, stipulations, and promises of blessings and curses. In this way, the covenants function as Scripture’s tectonic plates. And knowing their contents provides a growing awareness of the Bible’s message and how it leads to Jesus Christ. This perspective is vital for a fruitful daily Bible reading that respects the inspiration of Scripture.

The Christological Horizon: Delighting in God through the Person and Work of Christ

In Scripture, there is from the beginning a forward-looking orientation that leads the reader to look for Christ. That is to say, beginning with Genesis 3:15 when God promises salvation through the seed of the woman, all Scripture is written in italics — meaning, it slants forward towards the Son who is to come. As Jesus taught his disciples, all Scripture points to him (John 5:39), and so to interpret any portion of the Bible rightly, we must see how it naturally relates to Christ. This is what Jesus did on the Emmaus Road (Luke 24:27), and in the Upper Room (Luke 24:44–49), and what all his apostles continued to do and teach.

To see this method of reading the Old Testament and New Testament Christologically, one can look at the sermons in Acts. For instance, on the Day of Pentecost, Peter explains how the outpouring of the Spirit fulfills Joel 2 (Acts 2:16–21), the resurrection of Christ (Psalm 16; Acts 2:25–28), and the ascension of Christ (Psalm 110; Acts 2:34–35). Likewise, when Peter preaches on Solomon’s Portico in Acts 3, he identifies Jesus as the prophet like Moses prophesied in Deuteronomy 18:15–22 (see Acts 3:22–26). More comprehensively, when Paul is put under house arrest in Rome, Acts 28:23 records how the imprisoned apostle expounded the Scripture, “testifying to the kingdom of God and trying to convince them about Jesus both from the Law of Moses and from the Prophets.” Long story short, the sermons in Acts give many illustrations of how the apostles read the Old Testament Christologically.

Admittedly, this Christ-centered approach to interpretation can be misapplied or mischaracterized. But rightly understood, it shows how sixty-six different books find their unity in the Gospel of Jesus Christ.

The Bible is unified because it comes from the same God, and even more, it points to the same God-man, Jesus Christ. And because it is a human book with gracious promises to all humanity, all Scripture points to the long-awaited messiah who is the mediator between God and man.

To relate the three horizons, then, every text has a place in the covenantal framework of the Bible that leads us to Christ. Hence, every text is organically related to the covenantal backbone of Scripture, and every text finds its telos in Christ through the progress of Biblical covenants. And unless we bring these three horizons together, we fall short of understanding how to read Bible passages. At the same time, the order of the horizons matters too. Christ is not transported back in time to Israel, nor should we simply make superficial connections between the red color of the thread in Rahab’s window (Josh 2:18). Instead, we should understand the whole episode with Rahab (Joshua 2) in light of the Passover (Exodus 12), and then from the Passover, we can move to Christ.

This Christ-at-the-end (Christotelic) presupposition is based on the exegetical conviction that all Scripture, all covenants, all typology lead to Jesus. And, accordingly, it has massive interpretive implications. It says that no interpretation is complete until it comes to Christ. Any application that comes to us from the

Old Testament, which avoids the person and work of Christ, is fundamentally unsound. Equally, all New Testament applications find their source of strength in Christ, the covenant he mediates, and the Spirit

he sends. Therefore, all true interpretations of the Bible must be drawn from the text and related to the covenants, so that they bring us to see and savor Jesus Christ.

This is how we should read the Bible — over, and over, and over again!

Fear and Fear Not, but Take Up and Read

As we finish this field guide, I can imagine that the earnest follower of Christ or the individual considering the claims of Christ may feel inadequate for the task of reading the Bible. And, in a counterintuitive way, I want to affirm such feelings. Approaching God on Mount Sinai was daunting. And though we have a mediator available to us today in the person of Jesus Christ, it remains a gracious and fearful thing to approach God in his Word (Heb. 12:18–29). In this way, we should approach the Word of God with reverence and awe.

At the same time, with Christ living to intercede for those whom he is calling to himself, we should not fear. God deals mercifully with sinners who trust him and seek him in his Word. Thus, reading the Bible is not a fearful activity. So long as we come humbly before God, it is filled with grace, hope, life, and peace.

In truth, no one is, in and of himself, sufficient to read the Bible. All true Bible reading depends on the triune God communicating Himself to us and on us praying for grace to read God’s Word rightly.

In a world filled with endless distractions and competing voices, even the chance to engage in daily Bible reading is difficult. And thus, when we endeavor to pick up the Bible to read, we should do so with confidence that God can speak through the cacophony, and with prayer, asking God to help us. To that end, I offer this final word about Bible reading from Thomas Cranmer (1489–1556).

In a sermon on the place of reading Scripture, he emphasized the importance of repeated reading and the need to read Scripture humbly. As we read the Bible, let these words encourage us to understand it with patient humility and obedience, so that our profit from it results in praise to the living God who still speaks through it.

If we read once, twice, or thrice, and understand not, let us not cease so, but still continue reading, praying, asking of others, and so by still knocking, at the last the door shall be opened, as Saint Augustine says. Although many things in the Scripture are spoken in obscure mysteries, yet there is no thing spoken under dark mysteries in one place, but the selfsame thing in other places is spoken more familiarly and plainly to the capacity of both the learned and the unlearned. And those things in the Scripture that be plain to understand and necessary for salvation, every man’s duty is to learn them, to print them in memory, and effectually to exercise them; and as for the obscure mysteries, to be contented to be ignorant in them until time as it shall please God to open those things unto him. . . . And if you are afraid to fall into error by reading Holy Scripture, I shall show you how you may read it without danger of error. Read it humbly with a meek and a lowly heart, to think you may glorify God, and not yourself, with the knowledge of it; and read it not without daily praying to God, that he would direct your reading to good effect; and take upon you to expound it no further then you can plainly understand it. . . . Presumption and arrogance [are] the mother of all error: and humility needs to fear no error. For humility will only search to know the truth; it will search and will confer one place with another: and where it cannot find the sense, it will pray, it will inquire of others[s] that know, and will not presumptuously and rashly define anything which it knows not. Therefore, the humble man may search for any truth boldly in the Scripture without any danger of error.38, 39

—

Discussion & Reflection:

- Did any of this section help you know how to read Bible more faithfully?

- Which of the three horizons was most helpful to you?

- What’s your plan for how to regularly engage in daily Bible reading?

—

Endnotes

- Sometimes this view of God’s revelation ceasing at the end of the apostolic age is called cessationism. For a helpful discussion of this position, see Thomas R. Schreiner, Spiritual Gifts: What They Are and Why They Matter (Nashville: B&H, 2018), 155–69.

- For those interested in considering the Bible’s place in America, as well as its impact on the citizens of this nation, Mark Noll’s book, America’s Book: The Rise and Decline of a Bible Civilization, 1794–1911 (New York: Oxford University Press, 2022), is well worth the effort to read.

- Stephen J. Nichols, The Reformation: How a Monk and a Mallet Changed the World (Wheaton, IL: Crossways, 2007).

- Admittedly, his own theology had not crystallized in 1517. But by 1520, he had come to a place of understanding and affirming the five solas of the Reformation: Salvation is by grace alone, by faith alone, in Christ alone, according to Scripture alone, all for the glory of God alone. Hence, sola gratia, sola fide, solus Christus, sola Scriptura, and soli Deo Gloria.

- LW 32:112. Cited in Matthew Barrett, ed., Reformation Theology: A Systematic Survey (Wheaton IL: Crossway, 2017), ##.

- John Calvin, Institutes of the Christian Religion, ed. John T. McNeill, trans. Ford Lewis Battles (Louisville: Westminster John Knox, 1960), 1.7.5.

- Quoted in Barrett, Reformation Theology, 172.

- Richard N. Soulen, Handbook of Biblical Criticism, 2nd Ed. (Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox, 2011), 37.

- Paul Wegner, The Journey from Texts to Translations: The Origin and Development of the Bible (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2004), 101.

- The Torah, Naviim, and Ketuviim, make up the Tanakh, or the Hebrew Bible.

- Andreas Köstenberger, Darrell Bock, and Josh Chatraw, Truth Matters: Confident Faith in a Confusing World (Nashville: B&H Academic, 2014), 45.

- Today, the word “vulgar” is associated with crude or offensive speech, but in Latin the word vulgaris had to do with common, or of the masses. Hence, the Vulgate was a Bible written in common speech.

- F. F. Bruce, The Canon of Scripture (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity, 1988), 87–93.

- More exactly, he numbered twenty-two books of the Hebrew Bible, taking the Minor Prophets as one book, and other English books (e.g., 1–2 Chronicles and Ezra–Nehemiah) as one book also. We will revisit this way of numbering below.

- To be most precise, Jerome actually saw two kinds of books standing outside of Scripture — those that possessed an edifying effect for the church and others that were to be wholly avoided (Bruce, The Canon of Scripture, 90). Thus, he writes in the preface to his commentary on Proverbs, Ecclesiastes, and Song of Songs: “As the church indeed reads Judith, Tobit, and the books of Maccabees, but does not receive them among the canonical books, so let it read these two volumes for the edification of the people but not for establishing the authority ecclesiastical dogmas [i.e., church doctrine]” (Cited in Bruce, The Canon of Scripture, 91–92).

- Bruce, The Canon of Scripture, 98–100.

- Bruce, The Canon of Scripture, 101–04.

- Bruce, The Canon of Scripture, 105.

- Interestingly, Bruce points out that many Roman Catholic scholars do recognize the “deuterocanonical” nature of the Apocrypha (Bruce, The Canon of Scripture, 105). Nevertheless, Rome’s understanding of Scripture and tradition puts the Apocrypha on the same level as Scripture for deciding doctrine.

- Bruce, The Canon of Scripture, 51–54.

- Köstenberger, et al., Truth Matters, 52–53.

- Cited by Bruce, The Canon of Scripture, 228

- The Muratorian Canon (ca. AD 190) listed twenty-one books from the New Testament. Bruce, The Canon of Scripture, 158–69.

- Bruce, The Canon of Scripture, 50.

- Jerome, Epistle 53.9. Cited in Bruce, The Canon of Scripture, 225.

- B. B. Warfield, “‘It Says:’ ‘Scripture Says:’ ‘God Says,’” in The Inspiration and Authority of the Bible, and (Phillipsburg, NJ: P&R, 1948), 299–348.

- Biblical theology can be defined as “the discipline of letting Scripture interpret Scripture and reading the whole Bible according to its own literary structures and unfolding covenants.” https://christoverall. com/article/concise/the-butterfly-effect-how-Biblical-theology-makessystematic-theology-more-or-less-Biblical/

- Stephen Dempster, Dominion and Dynasty: A Theology of the Hebrew Bible (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity, 2003), 35.

- Following Roger Beckwith, The Old Testament Canon of the New Testament (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1984), Dempster, Dominion and Dynasty, 35, writes, “The oldest order was clearly that of the Hebrew canon, and there is strong evidence that this was the Bible of Jesus Christ.”

- My study Bible of choice would be the ESV Study Bible.

- Bible surveys provide information about the author, audience, and aim of every book in the Bible. Two excellent Bible surveys are Tremper Longman III and Raymond Dillard, An Introduction to the Old Testament (Grand Rapids: Zondervan Academic, 2006), and D. A. Carson and Douglas J. Moo,

An Introduction to the New Testament (Grand Rapids: Zondervan Academic, 2005). - Kevin J. Vanhoozer, Pictures at a Theological Exhibition: Scenes of the Church’s Worship, Witness, and Wisdom (Downers Grove, IL: IVP Academic, 2016), 79–80.

- These “three horizons” have alternatively been labeled textual, epochal, and canonical.

- David Schrock, The Three Most Important Words I Learned in Seminary: “Textual, Epochal, Canonical” 9Marks, https://www.9marks.org/article/ the-three-most-important-words-i-learned-in-seminary-textual-epochalcanonical/.

- For a selection of good Bible reading plans, see the multiple reading plans offered by the ESV Bible Translation. Additionally, I have found Scripture Union’s E-100 (Essential 100 Challenge) reading plan to be the best place to introduce someone to the whole Bible. In 100 selections from the Bible, it leads the reader through the whole canon of Scripture.

- Scott Redd, “Deuteronomy,” in A Biblical-Theological Introduction to the Old Testament, ed. Miles Van Pelt (Wheaton, IL: Crossway, 2016), 141; Dennis Johnson, Him We Proclaim: Preaching Christ from All the Scriptures (Phillipsburg, NJ: P&R, 2007), 167–97.

- I prefer covenantal as it focuses on the Bible’s own terms, covenants instead of epochs.

- Cited in Barrett, Reformation Theology, 184.

About the Author

DAVID SCHROCK is pastor for preaching and theology at Occoquan Bible Church in Woodbridge, Virginia. David is a two-time graduate of The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary. He is a founding faculty member of theology at Indianapolis Theology Seminary. He is also the editor-in-chief of Christ Over All and author of multiple books, including The Royal Priesthood and Glory of God. He blogs at DavidSchrock.com.

Table of Contents

- Part 1: What Is the Bible?

- According to the Confessions

- According to the Canon

- According to the Testimony of the Spirit

- Discussion & Reflection:

- Part 2: Where Did the Bible Come From?

- Old Testament

- New Testament

- Why the Canon Matters

- Discussion & Reflection:

- Part 3: What Is (Not) in the Bible?

- Discussion & Reflection:

- Part 4: How Should We Read the Bible?

- Preparing to Read the Bible: Cultivating a Heart for God’s Word

- The Textual Horizon: Discovering the Meaning of the Text

- The Covenantal Horizon: Discerning the Storyline of God’s Covenant History

- The Christological Horizon: Delighting in God through the Person and Work of Christ

- Fear and Fear Not, but Take Up and Read

- Discussion & Reflection:

- Endnotes

- About the Author