#18 God’s Plan: How to Discern His Will for Your Life

Introduction: Decisions

Some researchers estimate that an adult makes about 35,000 decisions every day. I don’t know how to prove a number like that, but it’s self-evident that you are constantly deciding what to do. You make most decisions rapidly, like whether to look this way, move that way, think this thought, or say that word. Many of your decisions are relatively small, such as what to eat or what to wear. Some of your decisions are moral, such as how to behave in a particular situation. Your rarest decisions are big ones, such as whether to marry a particular person or choose a specific career.

When it is time to decide what to do for more weighty decisions, some people are so eager to act that they skip the “ready” and “aim” steps of “ready, aim, fire.” Others who are more indecisive may spend so much time on the “ready” and “aim” steps that, in their great caution, they hesitate to ever pull the trigger. They feel paralyzed, as if a wizard from the world of Harry Potter cast the Petrificus Totalus spell on them — a full-body bind curse.

Why do some people freeze up when it’s time to make a decision? One reason is analysis paralysis: “There are multiple options, and I want more information before I decide.” Another reason is that they hesitate to commit because they like having options. I am not talking about FOMO — the fear of missing out. I am talking about FOBO — the fear of better options. Some people tend to wait to commit to a decision because a better option might come along. For example, you might hesitate to respond to a dinner invitation for Saturday evening because you don’t want to miss out on something better. Or you might delay committing to attend a particular college because something more desirable might pop up at the last minute. Or you might pass on asking out an eligible young lady because maybe someday you will discover one who has even better looks and character.

Christians in particular may freeze up when it’s time to make a decision because they think God wants them to do something very specific, and they are afraid of making the wrong call. They may struggle with how to know God’s will and fear that if they make the wrong choice, then they will be outside God’s plan. This leads to a constant search for decision making Bible verses to find the “perfect” path. Let’s address that concern first, then decide what to do.

Audio Guide

Audio#18 God’s Plan: How to Discern His Will for Your Life

Does the Bible promise that God will reveal to you exactly what you should do in every particular situation?

Short answer: No. But what about Proverbs 3:5–6?

“Trust in the LORD with all your heart,

and do not lean on your own

understanding. In all your ways

acknowledge him, and he will make

straight your paths.”

Does that passage promise that God will specifically direct or guide you to make a particular choice when you are at a crossroads? Christians commonly cite Proverbs 3:5–6 as their go-to Bible passage on how to know God’s specific will in a matter for a big decision:

– Where should you go to college? Or should you go to college at all?

– Whom should you marry?

– Which church should you join?

– What job should you have?

– What city or town should you live in?

– What home should you buy (or rent)?

– What car should you buy?

– Should you move to a different place?

– How should you invest your money?

– How should you invest the rest of your life when you are retired?

What Is the Subjective View of Finding God’s Will?

According to a common view of finding God’s individual will for your life (which I am calling the subjective view), if you trust in the Lord, then he will make it clear to you exactly what choice you should make. How? Through Scripture, the Spirit’s inner testimony, circumstances, counsel, your desires, common sense, and/or supernatural guidance, like impressions and a feeling of peace. Supernatural guidance is what adherents of this view tend to focus on, with the result that the key to knowing what to do is not that you carefully use your mind to wisely analyze a situation based on principles God has revealed in the Bible. The key is that you wait on God to fill you with leadings, impressions, promptings, and feelings. Garry Friesen concisely summarizes the subjective view with four statements:

- Premise: For each of our decisions, God has a perfect plan or will.

- Purpose: Our goal is to discover God’s individual will and make decisions in accordance with it.

- Process: We interpret the inner impressions and outward signs through which the Holy Spirit communicates his leading.

- Proof: The confirmation that we have correctly discerned the individual will of God comes from an inner sense of peace and outward (successful) results of the decision.1

This subjective view about discerning or finding God’s Will is like a modified version of the Urim and the Thummim. Under the Mosaic covenant, the leaders of God’s people could ask God to reveal his specific will in a matter and might get a straight-up Yes or No answer to a direct question with the Urim and the Thummim (e.g., 1 Sam. 14:41–42). The answer was objective and clearly divine. No feelings needed. But we are no longer under the Mosaic covenant, and this subjective view about trusting God and knowing his will is neither objective nor clearly divine.

Instead of searching for mysterious signs from God, we must recognize that the search for God’s

direction in the new covenant takes a different form. Many believers find themselves caught in a cycle of overspiritualizing every choice, rather than leaning on the wisdom found in Proverbs 3:5-6. The call is to move from a place of anxiety to one of walking by faith, understanding that God’s plan is often revealed through the renewal of our minds rather than through mystical objects.

The subjective view is misguided for at least six reasons:

1. The Bible is sufficient for knowing, trusting, and obeying God.

Andrew Murray (1828–1917) represents the subjective view when he says, “It is not enough for us to have the Word and to take out and apply that which we think we ought to do. We must wait on God for guidance, to know what He would have us to do.”2

But God gave us the Bible to guide us. The subjective view undermines the sufficiency of Scripture. People who follow the subjective view are not necessarily rejecting the sufficiency of Scripture; they are simply living inconsistently with it. The subjective view expects God to guide you to make specific choices by filling you with leadings and impressions and promptings and feelings, but God never promises to do that for you. Instead, God has revealed his will sufficiently in the Bible to help you live wisely. The sufficiency of Scripture means that the Bible is entirely sufficient for its purpose — for you to know, trust, and obey God (see 2 Tim. 3:16–17). The Bible’s purpose is not to directly answer every question you can ask. The Bible’s primary purpose is to reveal God so that you can know and honor him.3

The reward of Proverbs 3:5–6a is that God “will make straight your paths” (Prov. 3:6b). The idea is that God will clear out the obstacles for you so that you can successfully go forward on the right path. There are only two paths you can go down: the path of the wicked or the path of the righteous (Prov. 2:15; 11:3, 20; 12:8; 14:2; 21:8; 29:27). The wrong path is morally crooked; the right path is morally straight. The straight path is the rewarding path. For God to make your paths straight means that he enables you to live wisely and then enjoy the rewards that result from living wisely. Proverbs 3:5–6 does not teach that God will direct or guide you with special revelation outside the Bible. The Bible is sufficient for knowing, trusting, and obeying God.

2. The Bible has authority over your impressions and feelings.

The subjective view leads you to more highly value your own sense of God’s will over what God has actually revealed in the Bible to be his will. The focus is your subjective sense — not what God has objectively spoken.

It’s not necessarily wrong to decide what to do based on your gut feeling or intuition in a situation. But you don’t need a spidey sense to confirm that you are doing what God wants you to do. You don’t need to feel a special sense of peace before you decide what to do. What you need is wisdom based on what God has revealed in the Bible. Hearing God’s voice clearly happens through the pages of Scripture rather than through shifting emotions.

Some think Paul’s command in Colossians 3:15 supports the subjective view: “Let the peace of Christ rule in your hearts.” But in the literary context (Col. 3:11–15), Paul is not directing that you, as an individual Christian, should decide what to do based on whether you feel peace in your heart. Paul is directing how the community of believers should treat one another — similar to his exhortation in Ephesians 4:3 to be “eager to maintain the unity of the Spirit in the bond of peace.” In this way, Thy will be done as the church lives in unity, not as individuals chase internal feelings.

What if your subjective sense of what you should do contradicts God’s words? For example, the Bible plainly says, “This is the will of God, your sanctification: that you abstain from sexual immorality” (1 Thess. 4:3). What if you sense that, in your special case, God wants you to have sex with someone to whom you are not married (or that God wants you to date and marry a non-Christian)? What if you have a strong impression that God told you to do that? What if your conscience is clear about it? In such a case, your conscience may be clear but wrongly calibrated.4 God’s clear and sufficient Word has authority over your impressions and feelings. To follow God’s Will is to follow what He has already commanded.

What if you are choosing between two or more good options? You don’t need to cast lots or lay out a fleece or seek a subjective impression or dream or vision or angelic message or sign or still small voice or predictive prophecy. The Bible records instances of God speaking to individuals in isolated, clear, specific, miraculous, God-initiated ways — like Moses and the burning bush in Exodus 3. But those instances are unusual. They are not a paradigm for how we should make decisions.

God can obviously do whatever he wants, so I’m not saying he can’t communicate to us in any way except the Bible. But that is not normal or necessary, so it is misguided to prioritize seeking signs from God or direct leading outside the Bible. Even if you are waiting on the Lord for a big answer, that guidance does not carry the authority of Scripture. You should not treat such communication the same way you treat the sufficient Scripture because you can’t be certain that such communication actually comes from God, nor can you be certain that you are interpreting such communication correctly. If you want to hear the voice of God for sure, then read the Bible. This is the foundation for walking by faith and finding God’s direction. The Bible has authority over your impressions and feelings.

3. The Bible emphasizes that you should trust God’s wisdom that he has already revealed.

The subjective view leads you to focus on getting God to direct or guide you with fresh revelation about what to do in a specific situation, rather than trusting the wisdom God has already revealed in the Bible. But the literary context of Proverbs 3:5-6 does not contrast using my mind with mystically waiting on the Lord to bypass my mind. The contrast is between trusting my own wisdom versus trusting God.

Our problem is that we sinfully trust our own wisdom. It’s like if I arrogantly try to make sourdough bread on my own while disregarding my wife’s expert instructions. When we insist on trusting our own wisdom, we are being foolish and rebellious. We should trust God’s Will. In the book of Proverbs, the way we know God’s wisdom is by listening to God’s instructions. We access that in the Bible. We trust in the Lord by studying what God has spoken and then obeying it with his help. That’s why Christians memorize, study, sing, pray, and obey the Bible: the Bible is our main and final source for knowing God’s wisdom. We trust God’s words. We lean on God’s words. The Bible is filled with promises to trust and commands to obey. Focus on those (e.g., Rom. 12:9–21; Eph. 4:17–5:20) as you engage in a prayer for guidance.

The subjective view leads you to focus on what God has not revealed rather than on what God has. It leads you to obsess about choosing between two or more seemingly good options. Should you join this church or that church? Should you date this Christian or that Christian? Should you go to this school or that school? Should you take this job or that job? The Bible doesn’t directly answer those questions. God cares about all of these details, but he cares more about God’s plan for your holiness — that you love him with your whole being and love your neighbor as yourself and that you closely watch your life and doctrine (1 Tim. 4:16).

The subjective view leads you to be preoccupied with how to choose between good options instead of being preoccupied with believing and obeying the Bible. The subjective view presents God’s Will as if God has hidden it from you and made you responsible for finding and following it. Instead, we should find peace in Jeremiah 29 11, knowing that He is in control even when we don’t have a specific word for every small choice. Theologians help us here by distinguishing two aspects of God’s will. One aspect is what God would like to see happen (e.g., don’t murder), and another aspect is what God actually wills to happen (e.g., God predestined that people would murder Jesus — Acts 2:23; 4:28). Theologians distinguish these two ways that God wills with various terms — see Figure 1.5

| What God Would Like to See Happen (It Does Not Always Happen) | What God Actually Wills to Happen (It Always Happens) |

| Moral will: This is what we should obey. God tells us what is right and wrong. | Sovereign will: This is what God ordains. |

| Commanded will: This is what God commands. | Decreed will: This is what God decrees. |

| Revealed will: God tells us what we must do. | Secret or hidden will: God normally does not reveal his detailed plan to us ahead of time. (An exception is predictive prophecy such as Daniel 10.) |

Fig. 1. Terms That Distinguish Two Ways That God Wills

God reveals his moral will to us (Matt. 7:21; Heb. 13:20–21; 1 John 2:15–17), but God does not usually reveal his sovereign will to us (Eph. 1:11). So when we are trying to decide what to do, we should focus on obeying God’s moral or commanded or revealed will — not on finding his sovereign or decreed or secret/hidden will. Deuteronomy 29:29 puts those two aspects of God’s will right next to each other: “The secret things belong to the LORD our God, but the things that are revealed belong to our children and to us forever, that we may do all the words of this law.” You don’t need to be preoccupied with finding “the secret things” before you make a decision. Instead, you are responsible for obeying “the things that are revealed,” which involves using wisdom to make a decision. The Bible emphasizes that you should trust God’s wisdom that he has already revealed.6

4. The Bible emphasizes that you are responsible for making decisions.

God’s moral will includes not only how you should behave outwardly but what should motivate you inwardly. But it does not precisely specify everything for you. When you have viable options, the subjective view leads you to be more passive — to let God guide you with spontaneous ideas and feelings that are not based on much evidence or conscious thought.

It can be a convenient way to shift the blame off yourself and avoid taking responsibility for a challenging decision. It can be a hyper-spiritual excuse for being lazy instead of offering a prayer for guidance and then using your brain. But commands in the Bible presuppose that you are responsible for making decisions. And one of those decision making Bible verses is the command to “Get wisdom” (Prov. 4:5, 7).

Instead of waiting for a mystical nudge, we are called to a state of Faith over fear, actively engaging our minds in the pursuit of how to know Gods will. This process involves trusting God by applying the truths we already know. When we stop obsessing over signs from God for every mundane choice, we are free to practice walking by faith. We can be still and know that He is God, resting in the truth of Jeremiah 29 11 while we responsibly navigate the choices before us. When I was in school, I knew a guy who was dating a Christian young lady. They both loved the Lord and were above reproach in their character. As their dating became more serious, the lady decided to break up. The guy was confused because he didn’t understand why she was ending the relationship. All she would say is that she didn’t “have peace about” dating him any longer (which is better than saying that God told her to break up!). She used pseudospiritual jargon that implies, “Hey, don’t blame me. I’m just walking with the Lord and following his lead here.”7

Sometimes a pastor may adopt a subjective view, justifying his vision with some version of “God told me.” Even when that sort of testimony is well-intentioned, it can unfairly influence people. It can leave church members thinking, “Who am I to stand in the way of God? God himself specifically spoke to the pastor, so this is clearly God’s direction.” It can actually be manipulative when someone (especially a leader) elevates his subjective impressions (which may or may not be from the Lord) to a place beyond criticism or challenge.

When church leaders appeal to God’s private and special revelation as a pattern, others will imitate them. It leads to a guy telling a young lady, “God told me to marry you,” and the young lady replying, “No, he didn’t. He told me not to marry you.”

In these moments, we must return to the objective truth of Scripture. Instead of relying on conflicting impressions, we should engage in prayer for clarity and lean on the wisdom of Proverbs 3 5-6. True spiritual maturity involves trusting God enough to admit when we don’t have a direct word, and instead seeking God’s Will through the principles he has already laid out in His Word. Rather than claiming a direct line for every preference, we should walk by faith and allow the Bible to be the Lamp unto my feet, guiding our communal and personal decisions.

Contrast how Paul explains his decisions:

– “If it seems advisable [appropriate (NASB, NLT), fitting (LSB), suitable (CSB)] that I should go also, they will accompany me” (1 Cor. 16:4).

– “I think it is necessary to send back to you Epaphroditus” (Phil. 2:25 NIV).

– “When we could stand it no longer, we thought it best to be left by ourselves in Athens” (1 Thess. 3:1 NIV; cf. NASB, CSB).

– “I have decided to spend the winter there” (Titus 3:12).

Paul acknowledged his own agency in his decisions, and we would do well to follow his example. Instead of saying, “God told me to do this” or “God laid this on my heart” or “I sensed that God spoke to me,” it would be better to say, “I thought and prayed about it, and this seems wise to me.” Take responsibility for what you decide.

5. The subjective view is impossible to follow consistently.

If you make thousands of decisions every day, how can you possibly take the time to confirm that each one is exactly what God wants you to do? When you are getting dressed, why choose those socks?

When you are shopping, why choose that carton of eggs? When you enter a room with open seating,

why choose that seat? When you arrive at a gathering, why initiate a conversation with that person?

These are decisions you can’t responsibly spend all day contemplating. In practice, Christians who hold the subjective view have to follow it inconsistently, and they usually do so not for ordinary decisions

but only for what they consider the most important ones. (But sometimes what we think are ordinary decisions are more important than we realize — like choosing a seat that ends up being right next to

the person you eventually marry or talking to a stranger who connects you to a dream job.)

Even in these “ordinary” moments, trusting God means believing that his providence over our lives is secure. We do not need a specific prayer for guidance for every pair of socks because we know that God’s plan encompasses both the small and the great. Instead of being paralyzed by the need for a mystical sign, we can practice walking by faith, trusting that as we follow the principles of Proverbs 3 5-6, he is directing our steps. We can be still and know that even when we aren’t consciously seeking God’s direction for a specific seat, his sovereignty is at work in Gods timing.

6. The subjective view is historically novel.

Garry Friesen discovered that the subjective view

is actually a historical novelty. The obsession with certain guidance

that guarantees foolproof decisions appears to be a preoccupation peculiar to modern Christianity over the last 150 years. Prior to the writings of George Müller, there was virtually no discussion of “how to discover God’s will for your life” in the literature of the church. What I call the traditional view of guidance was an integral part of the theological culture of the Keswick Movement, which was very influential in England and America.8

The novelty of the subjective view does not decisively prove that it is wrong. But its novelty should at least give you pause about uncritically accepting it.

God has decreed a specific plan for your life, but he calls you to trust him and not worry about figuring out what his decreed plan is before you make a decision. This is the essence of Faith over fear. So if the Bible doesn’t promise that God will reveal to you exactly what you should do in every particular situation, how are you supposed to choose?

We must lean on the promise of Jeremiah 29 11, knowing that while God has a future and a hope for us, we find it by walking by faith in the light he has already given. Instead of being paralyzed by how to know Gods will, we should rest in the fact that trust in the Lord involves using the wisdom he has provided in His Word.

—

Discussion & Reflection:

- How would you summarize the subjective view of decision-making and God’s Will in your own words?

- What do you find clarifying and challenging in this evaluation of the subjective view?

—

Part 2: How to Decide? Four Questions

These four diagnostic questions are a set of principles to help you decide what to do (the principles are not steps one must take in a specific order):

- Holy Desire: What do you want to do?

- Open Door: What opportunities are open or closed?

- Wise Counsel: What do wise people who know you well and know the situation

well advise you to do? - Biblical Wisdom: What do you think you should do based on biblical wisdom?

1. Holy Desire: What do you want to do?

You might be thinking, “What kind of diagnostic question is it to ask what I want to do? Are you saying that if I want to do something sinful, I should do it?” No, this diagnostic question has an important caveat: Do what you want to do if you are joyfully loyal to the King. You should not do whatever you want if you are rebelling against God. If you are submitting to God — that is, if you are gladly following him, if you are obeying His moral will that he has revealed in the Bible — then do what you want to do. This is another way of saying what John MacArthur argues in his short book on God’s will: If you are saved, Spirit-filled, sanctified, submissive, and suffering according to God’s will, then do whatever you want.9

But definitely don’t do whatever you want if your life’s goal isn’t to glorify God. God calls you to make much of him as a faithful member of a disciple-making church. If you are a male, God calls you to make much of him as a faithful man — a son, brother, husband, father, and/or grandfather. If you are a female, God calls you to make much of him as a faithful woman — a daughter, sister, wife, mother, and/or grandmother.

This “holy desire” principle is based on Psalm 37:4:

“Delight yourself in the LORD, and he will give you the desires of your heart.”

Such desires are holy desires. If you are delighting in God, then what you want to do will align with God’s Will. If you are being selfish, then what you want to do will not align with what you should do. This is why Augustine says, “Love, and do what you want.”10 That is, do what you want if you are loving God with your whole being and loving your neighbor as yourself.

If you are contemplating whether to marry a particular Christian, for example, then it’s helpful to ask,

“Do you want to marry this person?” If such a prospect disgusts you (and if you are delighting in God), then that’s a sound indicator that you shouldn’t marry that person! Note what Paul says in 1 Corinthians 7:39: “A wife is bound to her husband as long as he lives. But if her husband dies, she is free to be married to whom she wishes, only in the Lord.” This means that (1) a Christian widow has the option to remarry or not, and (2) she may marry whomever she wants as long as the man is a Christian.

It’s notable that when Paul lays out the qualifications for a pastor or overseer, he begins like this: “If anyone aspires to the office of overseer, he desires a noble task” (1 Tim. 3:1). One of the criteria for a pastor is that he wants to be a pastor.11 What do you desire in your most holy moments as you engage in prayer for guidance? When we focus on trusting God, our desires often reflect God’s plan for our lives?

2. Open Door: What opportunities are open or closed?

Those who hold the subjective view may use the open door metaphor as an excuse in two ways.

First, it can be an excuse to do what you shouldn’t. For example, when a prestigious school offers you a scholarship or a company offers you a high-paying job, you walk through the “open door” even though there are good reasons not to. Second, it can be an excuse not to do what you should. For example, if you are unemployed and trying to find a job to provide for your family, instead of energetically and creatively seeking a job, you halfheartedly search and then loaf around because God hasn’t opened a door.

All I mean by “open door” or “closed door” is that an opportunity is currently an option or not. In other words, consider your circumstances. When my family lived in Cambridge, England for the first half of 2018, we explored some beautiful campuses, such as King’s College. But sometimes we couldn’t enter the grounds of a campus because the gates were locked. It’s frustrating when a locked door prevents you from entering where you desire to go. Locked doors narrow down your options at that time (I say

“at that time” because a door that is shut now may open at a later time).

The Bible uses the open door metaphor as a way of helping us decide what to do. Here is how Paul

shares his travel plans with the church in Corinth: “I will stay in Ephesus until Pentecost, for a wide door for effective work has opened to me” (1 Cor. 16:8–9a). Paul is planning to stay in Ephesus because God is opening up great opportunities to serve in a rich field of labor. This implies that if God were not opening up such a door that Paul’s travel plans would change.

But just because a door is open does not mean you should walk through it. Paul recounts to the Corinthians, “When I came to Troas to preach the gospel of Christ, even though a door was opened for me in the Lord, my spirit was not at rest because I did not find my brother Titus there. So I took leave of them and went on to Macedonia” (2 Cor. 2:12–13). Sometimes you may consider whether you should walk through an open door and then choose not to. An open door is an opportunity that you may or may not take. A closed door is not an option — though we may pray that God would open a particular door (see Col. 4:3–4).

So if you have diligently applied for several jobs and only three viable options are currently available and you need a job immediately, then those options are three open doors for now. You can’t walk through a closed door. All the closed doors have helped to narrow down your choices to three open doors at that time.

An open door does not signify that you should walk through it. Nor does a shut door signify that a particular opportunity will forever be closed for you. But when you are considering what to do, it’s helpful to observe what opportunities are currently viable options and which are not.

3. Wise Counsel: What do wise people who know you well and know the situation well advise you to do?

You may prefer to make big decisions independently, but it’s a mark of humility and wisdom to seek advice from godly and wise counselors:

– “Where there is no guidance, a people falls, but in an abundance of counselors there is safety”

(Prov. 11:14).

– “The way of a fool is right in his own eyes, but a wise man listens to advice” (Prov. 12:15).

– “Whoever walks with the wise becomes wise, but the companion of fools will suffer harm” (Prov. 13:20). – “Without counsel plans fail, but with many advisers they succeed” (Prov. 15:22).

– “Listen to advice and accept instruction, that you may gain wisdom in the future” (Prov. 19:20).

– “Plans are established by counsel; by wise guidance wage war” (Prov. 20:18).

– “By wise guidance you can wage your war, and in abundance of counselors there is victory” (Prov. 24:6).

What do wise people who know you well and who know your situation well counsel you about yourself and your goals? Listen carefully and humbly to their advice.

There’s a cunning way to try to rig advice — to selectively share only part of the relevant information and to solicit counsel from only people you sense will agree with what you want to do. The spirit of the proverbs above is that when you solicit advice from wise people, you do so with an open mind. Be a humble learner who is open to what wise people suggest. Don’t be a fool:

“The way of a fool is right in his own eyes, but a wise man listens to advice” (Prov. 12:15a).

So if you are considering whether to marry a particular Christian, what should you do if your parents, your pastors, and your closest friends warn you that they think this is a bad idea for various reasons? If all the advice aligns against what you were contemplating doing, then, as a general rule, such advice should give you serious pause about proceeding and lead you to reverse course.

This principle is especially helpful when all the counsel you receive is unified, and it aligns with both what you want to do and a door that God has providentially opened. This principle becomes less helpful when you consult wise people who both know you well and know the situation well, and yet advise you differently. For example, if you are contemplating whether to marry a particular Christian, what should you do if the counsel is roughly half in favor and half against? You’ll need to press into a fourth diagnostic question.

In these moments of conflicting advice, a sincere prayer for clarity is essential. This is where we must apply Proverbs 3 5-6, choosing to trust in the Lord rather than our own biased perception of the situation. Seeking God’s direction through a multitude of counselors is a biblical way of walking by faith, even when the path isn’t immediately clear. By remaining humble, you show that your primary desire is that Thy will be done, not your own.

4. Biblical Wisdom: What do you think you should do based on Biblical wisdom?

This diagnostic question is not perfectly parallel to the first three because it encompasses all of them.

The way of wisdom takes everything into account:

– your holy desire

– open and closed doors

– wise counsel

– God’s moral will he has revealed in the Bible

– other relevant information you may obtain by considering your gifts (what activities have proven fruitful?) and by researching (what are pros and cons of various options?)

God does not normally intervene in the lives of his people through direct, special revelation. God expects you to use biblical wisdom to make decisions.

King Jehoshaphat prayed, “We do not know what to do, but our eyes are on you” (2 Chron. 20:12b). There will be many times in your life when you don’t know what to do. But you can pray! Specifically, you should ask God for wisdom: “If any of you lacks wisdom, let him ask God, who gives generously to all without reproach, and it will be given him” (James 1:5). When you are praying about what you should choose in

a particular situation, you should not focus on receiving special revelation or impressions or leadings. Instead, focus on gaining wisdom.

But what exactly is wisdom? The essence of wisdom is skill or ability. Here are four illustrations:

- Joseph is wise in that he can skillfully govern Egypt (Gen. 41:33).

- Bezalel is wise in that he is skillful at craftmanship and artistic designs (Exod. 31:2–5).

- Hiram is wise in that he can skillfully make any work in bronze (1 Kings. 7:13–14).

- The people of Israel are wise in that they are skillful at sinning! Jeremiah sarcastically says,

“They are ‘wise’—in doing evil!

But how to do good they know not” (Jer. 4:22).

A man is wise in Proverbs in that he can skillfully live. So we may define wisdom like this: Wisdom is the skill to live prudently and astutely (prudent means “acting with or showing care and thought for the future,” and astute means “having or showing an ability to accurately assess situations or people and turn this to one’s advantage”.12

For example, a wise man does not merely understand that the speech of a forbidden woman drips honey and is smoother than oil and that in the end she is sharp as a two-edged sword and that her feet go down to death (Prov. 5:3–5). A wise man skillfully applies that knowledge by keeping his way far from her (5:8) and by drinking water from his own well (5:15). Wisdom is the skill to live prudently and astutely.

So when you are trying to decide what to do in a particular situation, you need Bible-saturated wisdom. You need discernment to understand and apply God’s moral will.

– That is why Paul commands you, “Try to discern what is pleasing to the Lord. … Do not be foolish, but understand what the will of the Lord is” (Eph. 5:10, 17). “Be transformed by the renewal of your mind, that by testing you may discern what the will of God is, what is good and acceptable and perfect” (Rom. 12:2).

– That is why Paul prays like this: “that your love may abound more and more, with knowledge and all discernment, so that you may approve what is excellent” (Phil. 1:9–10; cf. Col. 1:9).

When it comes to guidance, the Bible emphasizes right thinking, not fuzzy feelings. You need wisdom to understand what God commands in the Bible and then apply it in specific cases.

This is why it is so important that we read the Bible carefully and not mishandle it. If you go to the Bible for guidance by randomly flipping to a passage and reading it out of context, you are not interpreting and applying the Bible carefully. Instead, you are acting rashly and foolishly.13

This is not only the case with big decisions like whom to marry or what job to take. It’s also the case for making an ethical decision, which requires moral reasoning:

– How should you think about romantically touching your girlfriend or boyfriend prior to marriage?

– Should you and your spouse use contraception in marriage?

– Should you get a tattoo?

– Should Christians vote? If so, how? May a Christian in America vote for a Democrat at the

level of president, Congress, or governor?

– Should you wear particular clothes or not?

– Should you spend a free evening watching a particular show or movie?

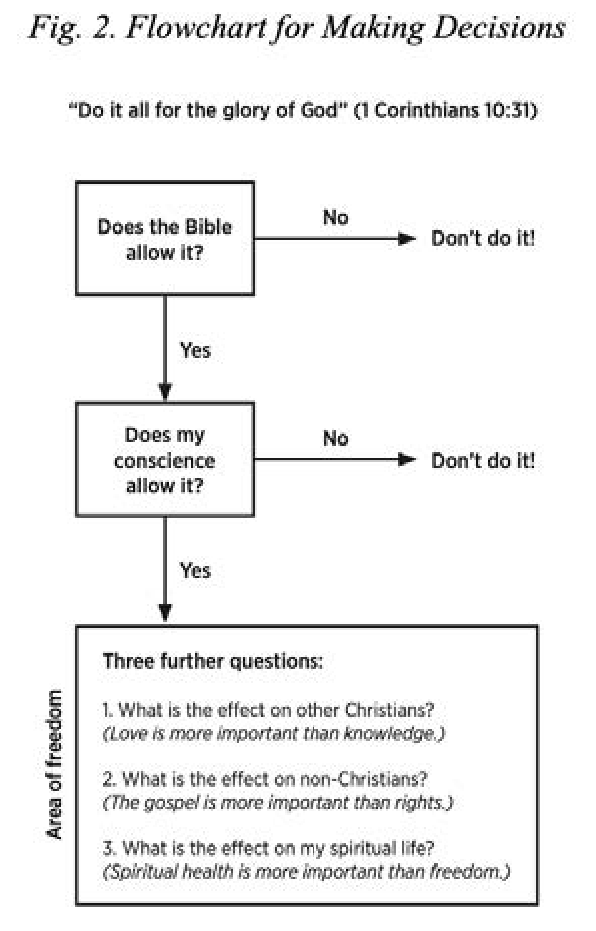

The flowchart by Vaughan Roberts summarizes how Christians should make ethical decisions based on principles in 1 Corinthians 8–10 (see Fig. 2):

Fig. 2. Flowchart for Making Decisions

The initial question is “Does the Bible allow it?” If the Bible forbids a particular activity, such as having sex outside of marriage, then don’t do it. Hard no. Not debatable.

The next question is “Does my conscience allow it?” In other words, “Can I thank God for it?” If your answer is Yes, then we could add another question here in the flowchart: Do you need to calibrate your conscience to align with God’s Word? Your conscience is your consciousness or sense of what you believe is right and wrong.15 Your conscience can’t make a sinful activity (like getting drunk) permissible, but it can make a permissible activity (like drinking wine in moderation) sinful if your conscience condemns you for doing it.

The final three questions explore areas of freedom. They emphasize that you and your individual liberties are not the only factors to consider. A mark of maturity and godliness is that you choose what to do based not only on how it may affect you but on how it may affect others.

There are four diagnostic questions that can help you decide what to do:

- Holy Desire: What do you want to do?

- Open Door: What opportunities are open or closed?

- Wise Counsel: What do wise people who know you well and know the situation well

advise you to do? - Biblical Wisdom: What do you think you should do based on Biblesaturated wisdom?

After you have worked through those four questions and decided what to do, then what?

—

Discussion & Reflection:

- Are there decisions you’re currently facing that would benefit from these four diagnostic questions?

- Does the description of wisdom above align with how you’ve thought about it, or is this a new approach to wisdom for you? What are some areas in your life that require you to exercise biblical wisdom?

—

Part 3: Make a Decision and Press On

Don’t freeze up. Don’t overanalyze. Don’t anxiously fear that you might miss the center of God’s will. Don’t obsess that you might experience something unpleasant. Instead, as Kevin DeYoung exhorts, “Just do something.”16 Make a decision, and press on. Don’t “let go and let God.” Instead, as J. I. Packer puts it, “Trust God and get going.”17

When you make a decision, you may be tempted to be anxious, sulky, inflexible, overthink, and cowardly. Here’s what to do instead.

1. Don’t be anxious. Trust God.

Jesus commands you, “Do not be anxious about your life, what you will eat or what you will drink, nor about your body, what you will put on” (Matt. 6:25). God feeds the birds, and you are more valuable than they (6:26). Worrying won’t help you live longer (6:27), and it will actually make you less holy and less happy. Anxiety is counterproductive. God magnificently clothes the lilies, and he will also clothe you (6:28–30).

So instead of worrying about what you’ll eat or drink or wear (or what person you will marry or what school you will attend or what job you will work or what kids you will have or where you will live or when you will die), seek God’s kingdom and righteousness first, and God will take care of the rest (6:31–33). Don’t worry about the future because “each day has enough trouble of its own” (6:34b NIV). This is the heart of Faith over fear.

Proud people worry. Humble people do not. And the way you humble yourself is by casting all your anxieties on God: “Humble yourselves, therefore, under the mighty hand of God so that at the proper time he may exalt you, [by] casting all your anxieties on him, because he cares for you” (1 Pet. 5:6–7).

This act of surrender is a vital prayer for clarity in our lives.

The opposite of being anxious is trusting God. Do you trust him? Do you trust God even when he doesn’t tell you all the reasons for what he does? Do you trust God’s character based on how God has revealed Himself to you in Scripture? Choosing to trust in the Lord means believing in Jeremiah 29:11—that He has a future and a hope for you, even when the path is not yet visible. It means waiting on the Lord with a heart at peace, knowing that Gods timing is perfect. God’s words make you wise and provide the ultimate God’s direction.

This might be hard for you because you want to know the future. You don’t know the future, and that’s okay because God does. He has ordained everything. And he’s got you covered. He’s taking care of you, and he has given you exactly what you need to please him. “We know that for those who love God all things work together for good, for those who are called according to his purpose” (Rom. 8:28). “All things” includes all of your decisions — wise and unwise.

When you fret about the future, you are distrusting God and thus dishonoring God. You don’t need to know every detail about what’s coming; you simply need to rest in God’s plan. This is the essence of choosing Faith over fear. You need to trust and obey God. And that includes not worrying about tomorrow, but rather waiting on the Lord with a confident heart. Trusting God means believing that even when we don’t see the way, he is a Lamp unto my feet for the very next step.

As you navigate the unknown, let your heart be anchored in Jeremiah 29:11. You can be still and know that he is in control of Gods timing. Instead of seeking a map of the entire journey, practice walking by faith one day at a time, knowing that his grace is sufficient for every decision you face.

2. Don’t be sulky. Be holy and happy.

You can become so preoccupied with discerning what God’s will is for a particular decision (like whether to accept a job offer) that you minimize what Scripture explicitly says about God’s will. For example, two passages in the Bible explicitly say, “This is the will of God”:

– “This is the will of God, your sanctification [God’s will is for you to be holy (NLT)]: that you abstain from sexual immorality” (1 Thess. 4:3).

– “Rejoice always, pray without ceasing, give thanks in all circumstances; for this is the will of God in Christ Jesus for you” (1 Thess. 5:16–18).

God’s will is not for you to be sullen. It’s for you to be holy and happy. In C. S. Lewis’s The Voyage of the Dawn Treader, do you remember how bad-tempered Eustace is before Aslan de-dragons him? Don’t be sulky like Eustace. God’s will is precisely the opposite for you. He wants you to be holy and happy. You please God by obeying him,18 and you are happiest when you live according to God’s design — when you enjoy God and his gifts.19

3. Don’t be inflexible. Be willing to adjust your plans.

You’ve got to make decisions — some of which should be inflexible, like a moral decision not to commit adultery. But in many other areas, you have freedom to honor God by choosing this or that — whether to eat at Chipotle or Chick-fil-A, whether to read The Pilgrim’s Progress or The Lord of the Rings, whether to stay at home or to travel, whether to attend school full-time or to work full-time.

As you plan what to do, remember that you are not God:

Come now, you who say, “Today or tomorrow we will go into

such and such a town and spend a year there and trade and make a profit”— yet you do not know what tomorrow will bring. What is your life? For you are a mist that appears for a little time and then vanishes. Instead, you ought to say, “If the Lord wills, we will live and do this or that.” As it is, you boast in your arrogance. All such boasting is evil. (James 4:13–16)

Don’t be proud after you make a decision. If you made a wise decision, then God gave you that wisdom. And sometimes after you make a decision, you have to revise your plan in light of circumstances you didn’t foresee. Many of your decisions are alterable, so be willing to adjust them. Your plans will come

to pass only by God’s Will. Don’t be inflexible.

Learning to say “Thy will be done” in our planning is a core part of walking by faith. It requires us to have trust in the Lord even when our carefully laid plans are disrupted. This posture helps us maintain Faith over fear because we realize that our life is a mist, but God’s plan is eternal. When we hold our plans loosely, we are better prepared for Gods timing, knowing that he is the one who ultimately provides God’s direction.

4. Don’t overthink past decisions. Strain forward to what lies ahead.

Don’t spend your short life wondering, “But what if I had chosen differently?” Be like Paul:

“One thing I do: forgetting what lies behind and straining forward to what lies ahead, I press on

toward the goal for the prize of the upward call of God in Christ Jesus” (Phil. 3:13–14).

Of course, you should learn from your mistakes. That’s what wise people do. But you shouldn’t obsess over the past. Paul presses on toward the goal by not focusing on the past. This includes Paul’s past life before he became a Christian, his life as a Christian, and the good progress he has made as a Christian.

You may apply this principle responsibly to avoid overthinking past decisions. Instead of being preoccupied with what would have happened had you chosen differently, you should single-mindedly strain forward to what lies ahead. This is a practical way of trusting God with your history while walking by faith into your future. Make a decision, and press on.

When you stop looking back, you are free to focus on God’s plan for today. You can rest in the promise of Jeremiah 29 11, knowing that even your past missteps are covered by His grace. Rather than being stuck in “what ifs,” choose Faith over fear and move forward in the strength He provides.

5. Don’t be cowardly. Be courageous.

There may be an element of risk involved even when you make a God-honoring decision — like when Queen Esther resolved, “I will go to the king, though it is against the law, and if I perish, I perish” (Esther 4:16). You need courage to press on.20

If you are having a hard time picking which college to attend, you need courage to commit and then not fret about what you may be missing at another school. Choose wisely, and press on.

If you are a man considering whether to pursue a relationship with a particular woman in order to see if it would be fitting for you two to marry, you need courage because she might say “no.” Kevin DeYoung’s analysis and advice here is spot on:

When there is an overabundance of Christian singles who want

to be married, this is a problem. And it’s a problem I put squarely at the feet of young men whose immaturity, passivity, and indecision

are pushing their hormones to the limits of self-control, delaying the growing-up process, and forcing countless numbers of young women to spend lots of time and money pursuing a career (which is not necessarily wrong) when they would rather be getting married

and having children. Men, if you want to be married, find a godly gal, treat her right, talk to her parents, pop the question, tie the knot, and start making babies.21

I don’t mean to imply that only young men can sin and that young women can’t, and I recognize that there may be other mitigating factors — like feminism and cultural decay. My burden here is that some Christians have a subjective and lazy approach to marriage, and I think it’s wise to exhort men to courageously take the initiative and be responsible.

When you decide what to do, beware of a prosperity-gospel mindset. According to the prosperity gospel, God rewards our increased faith with increased health and/or wealth. But that perverts the gospel. The gospel is that Jesus lived, died, and rose again for sinners and that God will save you if you turn from your sins and trust Jesus. It’s not true that God always blesses his obedient people with health and wealth.

As you obey God, you may suffer. God doesn’t promise that your life will always be free from conflict, hardship, and trouble. To the contrary, the Bible says, “All who desire to live a godly life in Christ Jesus will be persecuted” (2 Tim. 3:12). In God’s good providence, it is normal for godly people to suffer — men like Job, Joseph, Daniel, Jeremiah, and Paul.

If you suffer, that does not necessarily signify that you made a bad decision. God does not promise that nothing bad will ever happen to you if you stay in the center of his will. But we can trust in the Lord that Christ will always be with us (Matt. 28:20) and that no person or thing can successfully be against us (Rom. 8:31–39). True Faith over fear means following God’s direction even when it leads through the valley of the shadow of death, knowing that God’s plan is for our ultimate good and His glory.

—

Discussion & Reflection:

- Which of these five items is most difficult for you? Why do you think that is? Is there a heart issue or wrong belief underlying that difficulty?

- If you’re reading this with a mentor, ask what major decisions he or she has made and how that process worked. What lessons did your mentor take away, what would be done differently now, etc.?

—

Conclusion: “I Was the Lion”

What would it be like to get glimpses into your life two, five, ten, twenty-five years from now? You might wish that God would interpret your past and reveal your future to you and explain how what’s happening right now fits in the big picture.

But that is not God’s normal way. You’re not supposed to make decisions by asking God to reveal your future. It will all make sense in due course. For now, your job is to trust God supremely and not yourself or anybody else. This is the essence of walking by faith, not by sight.

Instead of searching for a map of the next decade, we are called to be still and know that He is in control. When we stop obsessing over how to know Gods will for the distant future, we can focus on being faithful today. Trusting God means believing that Gods timing is perfect, even when the big picture remains a mystery to us. As we lean on Proverbs 3 5-6, we find that He doesn’t give us a crystal ball; He gives us His presence and His Word as a Lamp unto my feet for the very next step.

I love how C. S. Lewis portrays this truth in The Horse and His Boy when the lion Aslan talks to the boy Shasta. While Shasta thinks he is all alone, he complains, “I do think that I must be the most unfortunate boy that ever lived in the whole world. Everything goes right for everyone except me.” Lewis adds, “He felt so sorry for himself that the tears rolled down his cheeks.”22 Then Shasta suddenly realizes that someone was walking beside him in the pitch darkness. That someone is Aslan. When Shasta tells Aslan his sorrows, Aslan’s response should rebuke and encourage us of little faith:

[Shasta] told how he had never known his real father or mother and had been brought up sternly by the fisherman. And then he told the story of his escape and how they were chased by lions and forced to swim for their lives; and of all their dangers in Tashbaan, and about his night among the tombs, and how the beasts howled at him out

of the desert. And he told about the heat and thirst of their desert journey and how they were almost at their goal when another lion chased them and wounded Aravis. And also, how very long it was since he had had anything to eat.

“I do not call you unfortunate,” said the Large Voice.

“Don’t you think it was bad luck to meet so many lions?” said Shasta.

“There was only one lion,” said the Voice.

“What on earth do you mean? I’ve just told you there were at least two the first night, and—”

“There was only one, but he was swift of foot.”

“How do you know?”

“I was the lion.” And as Shasta gaped with open mouth and said nothing, the Voice continued. “I was the lion who forced you to join with Aravis. I was the cat who comforted you among the houses of the dead. I was the lion who drove the jackals from you while you slept. I was the lion who gave the Horses the new strength of fear for the last mile so that you should reach King Lune in time. And I was the lion you do not remember who pushed the boat in which you lay, a child near death, so that it came to shore where a man sat, wakeful at midnight, to receive you.”

“Then it was you who wounded Aravis?”

“It was I.”

“But what for?”

“Child,” said the Voice, “I am telling you your story, not hers. I tell no one any story but his own.”

“Who are you?” asked Shasta.

“Myself,” said the Voice, very deep and low so that the earth shook: and again “Myself,” loud and clear and gay: and then the third time “Myself,” whispered so softly you could hardly hear it, and yet it seemed to come from all round you as if the leaves rustled with it.

Shasta was no longer afraid that the Voice belonged to something that would eat him, nor that it was

the voice of a ghost. But a new and different sort of trembling came over him. Yet he felt glad too. …

After one glance at the Lion’s face, he slipped out of the saddle and fell at its feet. He couldn’t say anything, but then he didn’t want to say anything, and he knew he didn’t say anything.23

Direct encounters with God — like Aslan’s conversation with Shasta — are not normal. You don’t need

to seek them. God has already given you what you need to be faithful and fruitful. The above exchange between Shasta and Aslan should remind you that the all-knowing, all-powerful, all-good God is superintending all things for your good, and in this life, you won’t know all the ways and reasons God unfolds his plan for you. So don’t be anxious and sulky like Shasta. Trust God, and get going. Choose wisely, and press on.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to friends who graciously offered feedback on drafts of this little book, including John Beckman, Bryan Blazosky, Tom Dodds, Abigail Dodds, Betsy Howard, Trent Hunter, Scott Jamison, Jeremy Kimble, Cynthia McGlothlin, Charles Naselli, Jenni Naselli, Kara Naselli, Hud Peters, John Piper, Joe Rigney, Jenny Rigney, Adrien Segal, Katie Semple, Steve Stein, Eric True, and Joe Tyrpak.

End Notes

- Garry Friesen, with J. Robin Maxson, Decision Making and the Will of God: A Biblical Alternative to the Traditional View, 2nd ed. (Sisters, OR: Multnomah, 2004), 35. For a summary of the subjective view, see pp. 21–35. Friesen wrote his ThD dissertation on “God’s Will as It Relates to Decision Making” (Dallas Theological Seminary, 1978), and he has devoted scholarly attention to this issue for decades. What I am calling the subjective view, Friesen calls “the traditional view” since it was virtually the only view he heard people teach while he was growing up.

- Andrew Murray, God’s Will: Our Dwelling Place (Springdale, PA: Whitaker House, 1982), 76–77 (italics original).

- On the sufficiency of Scripture, see Stephen J. Wellum, Systematic Theology, Volume 1: From Canon to Concept (Brentwood, TN: B&H Academic, 2024), 338–49.

- See Andrew David Naselli and J. D. Crowley, Conscience: What It Is, How to Train It, and Loving Those Who Differ (Wheaton, IL: Crossway, 2016), 55–83.

- See Andrew David Naselli, Predestination: An Introduction, Short Studies in Systematic Theology (Wheaton, IL: Crossway, 2024), chap. 7 (pp. 111– 20). On God’s meticulous sovereignty and human responsibility, see chap. 6 (pp. 79–110).

- For advice on how this applies to getting married, see Douglas Wilson, Get the Girl: How to Be the Kind of Man the Kind of Woman You Want to Marry Would Want to Marry (Moscow, ID: Canon, 2022), 29–38.

- I later learned that her response was a bit misleading. She actually called it off because she had concerns about the guy’s character, but she didn’t want to communicate that to him. She wasn’t obligated to say that to the guy, but I understand why the guy was frustrated and perplexed. She hid behind a mystical veil of sanctified emotions instead of acknowledging a legitimate reason — she didn’t want to continue dating him because she didn’t think he was the type of man she wanted to vow to submit to and respect until death parts them. That is a lady’s prerogative. She has every right not to marry a guy if she thinks he is arrogant or incompetent or lazy or unattractive or annoying or wimpy or untrustworthy or whatever. She may well have been applying God’s moral will in a God-honoring way such that she concluded, “I don’t believe the Lord would have me marry you.”

- Garry Friesen, “Walking in Wisdom: The Wisdom View,” in How Then Should We Choose? Three Views on God’s Will and Decision Making, ed. Douglas S. Huffman (Grand Rapids: Kregel, 2009), 105. On Keswick theology, see Andrew David Naselli, No Quick Fix: Where Higher LifeTheology Came From, What It Is, and Why It’s Harmful (Bellingham, WA: Lexham, 2017).

- John MacArthur, Found: God’s Will; Find the Direction and Purpose God Wants for Your Life, 3rd ed. (Colorado Springs, CO: Cook, 2012).

- Augustine, Ten Homilies on the First Epistle of John, Homily 7 (on 1 John 4:4–12), §8.

- For how to discern if a man is called to pastoral ministry, see C. H. Spurgeon, “Lecture II: The Call to the Ministry,” in Lectures to My Students: A Selection from Addresses Delivered to the Students of the Pastors’ College, Metropolitan Tabernacle, Lectures to My Students 1 (London: Passmore and Alabaster, 1875), 35–65; James M. George, “The Call to Pastoral Ministry,” in Rediscovering Pastoral Ministry: Shaping Contemporary Ministry with Biblical Mandates, ed. John MacArthur (Dallas: Word, 1995), 102–105; Jason K. Allen, Discerning Your Call to Ministry: How to Know for Sure and What to Do about It (Chicago: Moody, 2016); Bobby Jamieson, The Path to Being a Pastor: A Guide for the Aspiring, 9Marks (Wheaton, IL: Crossway, 2021).

- New Oxford American Dictionary.

- For advice on how to interpret the Bible, see Andrew David Naselli, How to Understand and Apply the New Testament: Twelve Steps from Exegesis to Theology (Phillipsburg, NJ: P&R Publishing, 2017); D. A. Carson and Andrew David Naselli, Exegetical Fallacies, 3rd ed. (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, forthcoming).

- Vaughan Roberts, Authentic Church: True Spirituality in a Culture of Counterfeits (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2011), 133. Used with permission.

- See Naselli and Crowley, Conscience, 32–44.

- Kevin DeYoung, Just Do Something: A Liberating Approach to Finding God’s Will; or, How to Make a Decision without Dreams, Visions, Fleeces, Open Doors, Random Bible Verses, Casting Lots, Liver Shivers, Writing in the Sky, Etc. (Chicago: Moody, 2009).

- J. I. Packer, Keep in Step with the Spirit: Finding Fullness in Our Walk with God, 2nd ed. (Grand Rapids: Baker Books, 2005), 128. For a critique of “let go and let God” as a paradigm for Christian living, see Naselli, No Quick Fix.

- Cf. Wayne Grudem, “Pleasing God by Our Obedience: A Neglected New Testament Teaching,” in For the Fame of God’s Name: Essays in Honor of John Piper, ed. Sam Storms and Justin Taylor (Wheaton, IL: Crossway, 2010), 272–92.

- See John Piper, Desiring God: Meditations of a Christian Hedonist, 5th ed. (Wheaton: Crossway, 2025); Joe Rigney, The Things of Earth: Treasuring God by Enjoying His Gifts, 2nd ed. (Moscow, ID: Canon, 2024).

- Cf. John Piper, Risk Is Right: Better to Lose Your Life Than to Waste It (Wheaton, IL: Crossway, 2013); Joe Rigney, Courage: How the Gospel Creates Christian Fortitude, Union (Wheaton, IL: Crossway, 2023).

- DeYoung, Just Do Something, 108.

- C. S. Lewis, The Horse and His Boy, The Chronicles of Narnia (New York: HarperCollins, 1954), 161–62.

- Lewis, The Horse and His Boy, 164–66.

About the Author

ANDREW DAVID NASELLI (PhD, Bob Jones University; PhD, Trinity Evangelical Divinity School) is professor of systematic theology and New Testament at Bethlehem College and Seminary in Minneapolis and Lead Pastor of Christ the King Church in Stillwater, Minnesota. Andy and his wife, Jenni, have been married since 2004, and God has blessed them with four daughters.

Table of Contents

- What Is the Subjective View of Finding God’s Will?

- 1. The Bible is sufficient for knowing, trusting, and obeying God.

- 2. The Bible has authority over your impressions and feelings.

- 3. The Bible emphasizes that you should trust God’s wisdom that he has already revealed.

- 4. The Bible emphasizes that you are responsible for making decisions.

- 5. The subjective view is impossible to follow consistently.

- 6. The subjective view is historically novel.

- Discussion & Reflection:

- Part 2: How to Decide? Four Questions

- 1. Holy Desire: What do you want to do?

- 2. Open Door: What opportunities are open or closed?

- 3. Wise Counsel: What do wise people who know you well and know the situation well advise you to do?

- 4. Biblical Wisdom: What do you think you should do based on Biblical wisdom?

- Discussion & Reflection:

- Part 3: Make a Decision and Press On

- 1. Don’t be anxious. Trust God.

- 2. Don’t be sulky. Be holy and happy.

- 3. Don’t be inflexible. Be willing to adjust your plans.

- 4. Don’t overthink past decisions. Strain forward to what lies ahead.

- 5. Don’t be cowardly. Be courageous.

- Discussion & Reflection:

- Conclusion: “I Was the Lion”

- Acknowledgments

- End Notes

- About the Author